I guess from my standpoint the two terms "tax supported" and "free" are in opposition. Most of the so-called free libraries are supported by either donations or taxes. OCLC, the global library cooperative and sponsor of the WorldCat.org website, published a recent report about about the attitudes and perceptions about library funding. the report is entitled, From Awareness to Funding: A study of library support in America. OCLC summarizes the reports finding as follows:

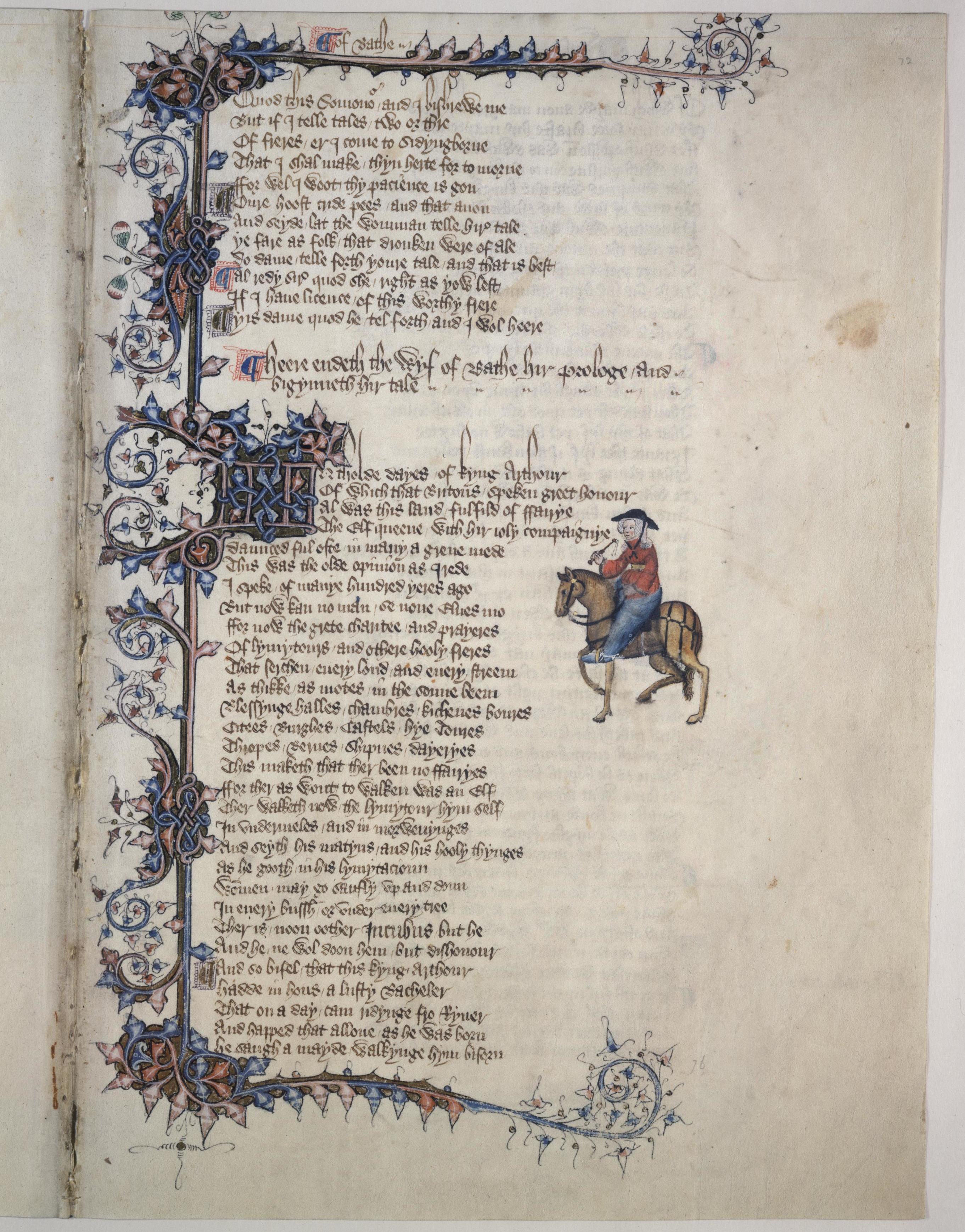

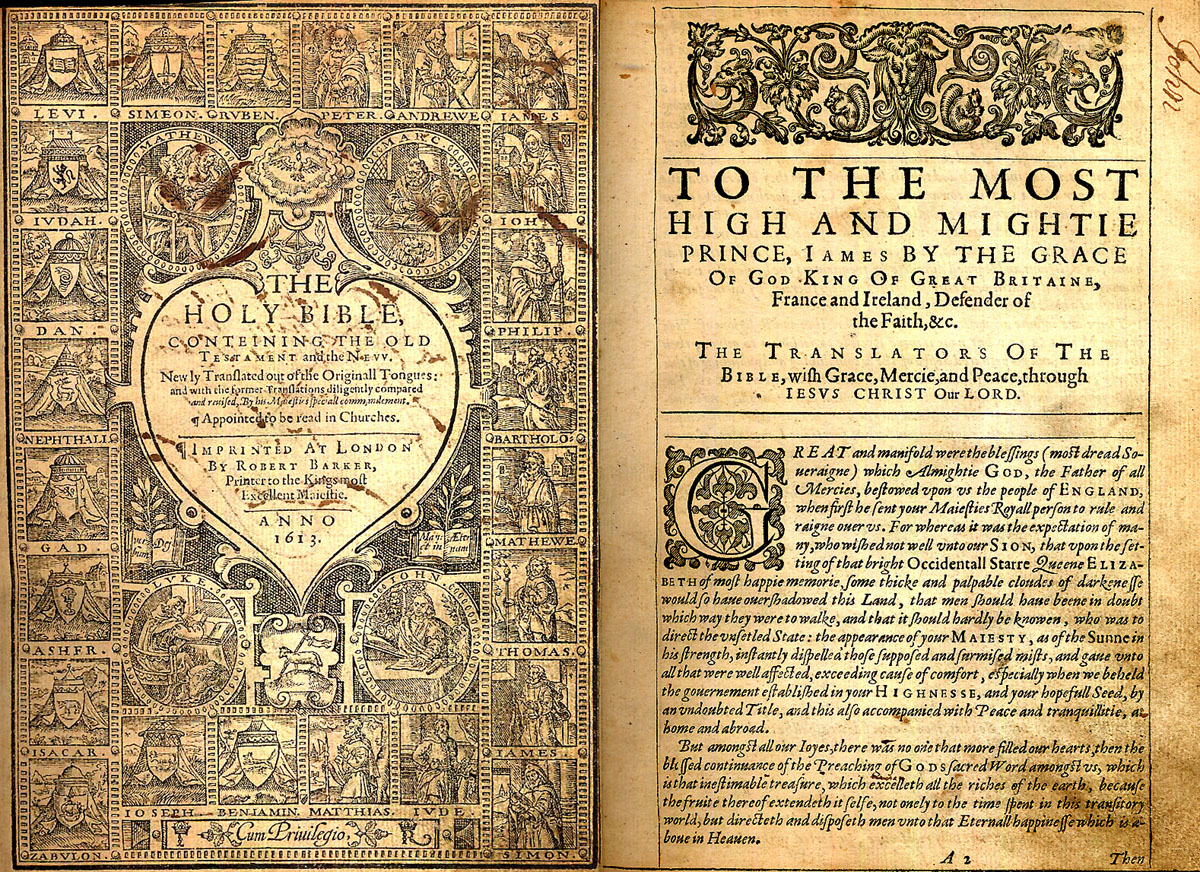

Many of the research sources used by genealogists come directly or indirectly from libraries and archives, both private and public. The distinction between an archive and a library is somewhat blurred. The definition of an archive can easily include a library. The question of who can use a particular library or archive is largely dependent on the supporting and operating entity either government or some privately owned institution or organization. For example, both the largest and the second larges genealogical libraries in the world are owned and operated by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, while the largest library in the world, The Library of Congress, is owned and operated by the United States Federal Government.The report suggests that targeting marketing messages to the right segments of the voting public is key to driving increased support for U.S. public libraries.

- Library funding support is only marginally related to library visitation

- Perceptions of librarians are an important predictor of library funding support

- Voters who see the library as a 'transformational' force as opposed to an 'informational' source are more likely to increase taxes in its support

When we refer to a "free public library," we are really talking about a library that is funded from public sources. One reference for the status of public library funding is a report by the American Library Association entitled, "Public Funding and Technology Access Study 2011-2012." Some of the findings of the ALA report seem to directly contradict the findings of the Pew Research Center report entitled, "Libraries and Learning." However, both reports are consistent in their assessment of the trends in library funding and usage. Quoting from the ALA report Executive Summary,

After more than four years of consecutive budget cuts, it is unclear whether libraries will be able to recover the funding needed to return to pre-recession levels of staffing, open hours, collections and technology services. While a segment of U.S. public libraries reported budget improvements, many libraries continue to grapple with the negative, cumulative effect of ongoing budget woes:For over 40 years, our family visited the public libraries in Scottsdale and Mesa, Arizona. The Mesa Public Library was an excellent facility. But our experience mirrors the trend. The number of employees in the library had dramatically decreased. Computer usage had increased but not at the rate of overall increase in computer usage in the general community. The Mesa Library is part of the Greater Phoenix Digital Library accessed through OverDrive.com. Acquisition of new material, books etc. had dramatically declined.

- Twenty-three states report cuts in state funding for public libraries this year. For three years in a row, more than 40 percent of states have reported decreased public library support.

- A majority of public libraries (56.7 percent) report flat or decreased budgets, a slight improvement from the 59.8 percent reported last year.

- Over 65 percent of libraries report an insufficient number of public computers to meet demand some or all of the time.

- Overall, 41.4 percent of libraries report that their Internet connection speeds are insufficient some or all of the time.

Now turning to the genealogical community, I would venture to say that a sizable portion of the world-wide genealogical community has not visited a library in the last year. I would also guess that there is a sizable number of genealogists who haven't set foot in a library since they were involved in formal education. So why should we care about the health of our American libraries at all?

When I worked at the Marriott Library of the University of Utah, I used to think it strange that the use of the library closely followed the school schedule. During breaks between the quarters (the U of U was on a four quarters a year system) and during Summer quarter, the usage of the library would plummet. The library would essentially be abandoned. It always seemed to me that if you were attending a university, you would cherish the opportunity to be in the library, especially when it was not so busy. I identified libraries with information and I identified the acquisition of information as the ultimate goal of education. I was attending the university to gain information (an education) so I spent as much time as possible cramming all of the information I could find into my head.

Genealogists deal in information. Libraries have information. Therefore genealogists should be very much involved in libraries. But now, we see a new paradigm. Information has become a commodity to be bought and sold on the open market. During most of my life, if I wanted to "research" something, anything, I had to go to a library. Therefore the subjects I would "research" had to be important enough to spend the time needed to go to the library and look up the answer to the question. When I had an interest in a specific subject, I would go to the library and read (or look through) every book they had on the subject.

As a genealogical researcher, I have many questions that cannot be answered by my local public library. I have questions that cannot be answered by the huge university library that I visit now several times a week. In fact, I have questions that cannot be answered by any library any where on the face of the earth. So now what?

Meanwhile, enter the Internet, stage left. If I have a question, I ask the Internet for the answer. Even trivial questions now are answered without much effort in a matter of seconds. But, I still have questions from my genealogical research that even the entire Internet cannot answer.

Let's compare yesterday and today.

- Yesterday if I wanted to read a book that I did not own, I went to a library

- Today, I can read almost any book I want without physically going to a library

- Yesterday, I went to a library to do research

- Today, I do nearly all my research from home. I can quickly determine if I need to go to a library for specialized collections.

- Yesterday, I went to the library to research how to fix my car, answer questions about travel, gardening and other activities.

- Today, I get almost all the information I want from the Internet.

You can see the trend. Here is the conclusion from the ALA report:

Libraries are part of the solution for those in search of the digital connection and literacy required by today’s competitive global marketplace. However, unless strategic investments in U.S. public libraries are broadened and secured, libraries will not be able to continue to provide the innovative and critical services their communities need and demand.

Now, if libraries are viewing themselves as providing the digital connection and literacy, what is their role in providing information services? Hasn't the Internet replaced libraries as a source of information?

Here are some more statistics from the Pew Research Center article entitled, U.S. Smartphone Use in 2015."

The traditional notion of “going online” often evokes images of a desktop or laptop computer with a full complement of features, such as a large screen, mouse, keyboard, wires, and a dedicated high-speed connection. But for many Americans, the reality of the online experience is substantially different. Today nearly two-thirds of Americans own a smartphone, and 19% of Americans rely to some degree on a smartphone for accessing online services and information and for staying connected to the world around them — either because they lack broadband at home, or because they have few options for online access other than their cell phone.I have commented recently on the prediction that within five years, 70 percent of the world's population will be using smartphones. See "6.1B Smartphone Users Globally By 2020, Overtaking Basic Fixed Phone Subscriptions." So, if libraries see themselves as providing digital connections, they will be marginalized by the fact that most of the world's population will be accessing the Internet through smartphones. The usage figures for the United States are significantly higher than the worldwide estimates, by the way.

Where can we look for actual usage figures that reflect this move from traditional information services such as public libraries to online data acquisition? Back to the Brigham Young University, Harold B. Lee Library. If you dig a little you can find the library statistics. The statistics show that since 2009 there has been about a 52% decrease in library usage. This is a major university library and we are not talking about the economy or funding or politics or any of the other possible causes of decline.

My personal opinion is that libraries as they are presently constituted will be unrecognizable in the not too distant future. They may well serve as cultural, social and even entertainment hubs, but the function of providing information has now moved to the Internet.

As a genealogist, if I can access online millions of records previously only available in libraries and particularly one library in Salt Lake City, Utah and if I can access most, or nearly all of the books about genealogy online, why would I visit a library? Or even need one?