|

| Heures de Notre-Dame, Bruges, about 1470 |

I have been fielding a lot of issues and questions lately about research into the Middle Ages. A quick example of how this subject can come up for genealogists is to think about the early immigrants to the American continents from Europe. For example, the first settlers in Jamestown, as part of the Virginia Company, arrived on May 14, 1607. The birth dates of the original 104 Jamestown Settlement Colony settlers and others who show up primarily in land records in the early 1600s are entirely missing even after 400 years of records and research. Likewise, the details of the early lives of the passengers of the Mayflower who arrived in 1620 are equally elusive. See the following:

McCartney, Martha W. 2000.

Documentary history of Jamestown Island. Williamsburg, Va: [Colonial Williamsburg Foundation].

General Society of Mayflower Descendants,

Mayflower families through five generations, Various authors and publication dates, usually known as the "Silver Books."

The Medieval Ages or Middle Ages are generally considered to be from about 1000 A.D. to around the end of the 15th Century. For a ballpark figure, I usually use 1550 A.D. as a general cut off date. For example, the earliest consistent parish registers in England begin in 1538 with the mandate from Henry VIII. So, if you think about it, almost all of the Jamestown settlers and most of the Mayflower passengers were born in the 1500s. It is no wonder that extending genealogical lines from America to Europe gets progressively more difficult as you go back in the past.

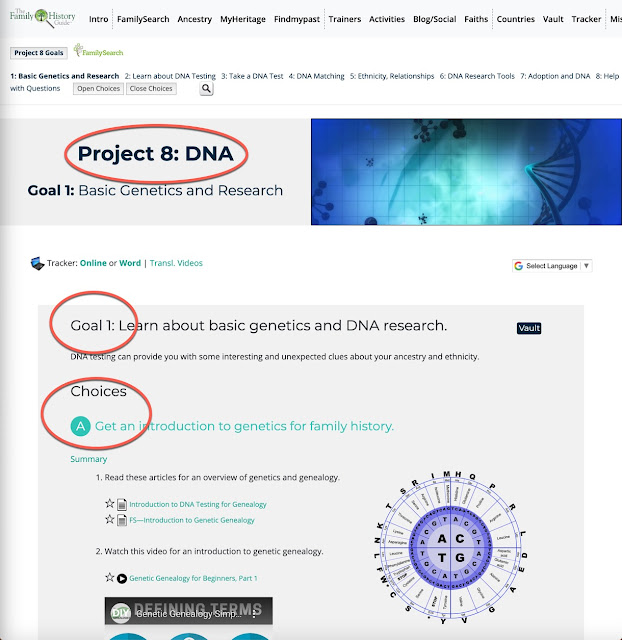

One reason for the change from the Medieval Age to the Renaissance was the invention of movable type by Johann Gutenberg and the publication of the first book in 1455. Notwithstanding these historical considerations and the paucity of records about individuals before 1500, many of the online pedigrees contain lines extending into the early 1500s and before. If you go into a website such as FamilySearch.org, you can easily find such pedigrees. Here is one example from my own lines.

It is also interesting that many of these people have no supporting sources listed. Where records are cited, they usually come from wills. Here is another line from the FamilySearch.org Family Tree that eventually goes back to 1175 with gaps where there are no sources listed.

I am quite certain that most of the complaints about changes to the Family Tree and about the battles being fought over the identity of certain ancestors deal mainly with people born before 1800 and increases with people born in the 1700s and the 1600s and continues to increase further back in time.

What if you wanted to get involved in researching names back into the 1500s and before? What would you need to know and what documents could you use to find information about any particular family line? Of course, the answer to this question can only be answered with specific examples. The existence of genealogical records for any family line depends on the time period involved and the availability of records. For example, you can go back much further in time in Spain than you can in Sweden. The oldest Swedish church record is a death record of 1608 – 1615 from the parish of Helga Trefaldighet in Uppsala diocese. See

Sweden Church Records. The oldest records in Spain go back to the early 1300s. See "

Legacy Tree Onsite: A Guide to Spanish Genealogy & Family History Resources."

The National Archives in Kew, Richmond, Surrey, England has published a helpful guide entitled, "

How to look for records of Medieval and early modern family history." It is published under the Open Government Licence for public sector information. I recommend reviewing this short document before you decided to get involved with Medieval records. Here is a quote from a section entitled, "

Reading medieval records."

Medieval records are generally much more difficult to use than those from the 16th century and later.

Note that:

- they are usually in a highly abbreviated form of Latin

- the use of English starts to become more common in informal documents in the late 15th century, but Latin was used in formal records until 1733 (except during the Interregnum)

- the handwriting and letter forms are very different from those of the present day alphabet

- the terminology and contemporary meanings of words may be difficult to understand

Use our tutorials on Reading old documents to help you decipher the records. Alternatively you may wish to consult published sources for further guidance. We will not translate or read documents on your behalf.

The first step in this process is to learn to read medieval Latin. Next, you need to learn to read the old handwriting involved. By the way, the difficulty in reading the handwriting involved in old records begins in the 1800s so you may need to work back slowly. Interestingly, almost all the controversy I encounter about pedigree lines as reflected in the Family Tree does not involve the interpretation of old documents, usually, the controversy comes from records inherited or copied from a book.

Oh, I think it is also important to understand that the amount of genealogically significant information available about anyone who was neither rich nor influential virtually disappears in the 1500s. When I am asked about disputes where there are people who have a "title" i.e. nobility, I automatically suspect that the information has little foundation or is entirely fabricated. I seldom turn out to be wrong. If you want to discuss this particular topic with me then before you start telling me about how reliable your grandmother or aunt was, I suggest you read the following book entirely from cover to cover.

Weil, François.

Family Trees: A History of Genealogy in America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2013.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674076341.

I guarantee that if you read this book, you will be a lot more skeptical about the accuracy of your inherited or "book-based" genealogy than you are now.

Now, to answer the question in the title of this post. Yes, there is genealogical information in Medieval Manuscripts but before you start relying on pedigrees that go back into the 1700s and beyond, I suggest you spend a considerable amount of time learning the history of the places you intend to research and then working back from a well-supported position on a pedigree in the mid to late 1800s and carefully documenting every generational step backward in time. As I have done this on many of my own lines, I have always been stopped in the 1700s with only a few rare exceptions going back to the 1600s.

If you are an expert in Medieval Records, I would like to have the privilege of meeting you and talking to you some time.