One overriding activity of research genealogists is locating pertinent historical records about their ancestors and relatives. The location of specific records is sometimes a mystery due to the movement of populations, changes in the jurisdiction of the entities maintaining the records and the movement of the records themselves due to storage or preservation concerns. One way to markedly assist researchers in locating applicable records is to accurately record the locations associated with the origination of the records.

From the standpoint of a genealogical researcher, the issue of recording locations revolves around the traditional rule that places be identified and recorded as they existed at the time an event occurred. Although the rule has become a “standard” there are a significant number of genealogists who believe that the event should be recorded as it is today. The main problem with this point of view is that, over time, the designation of a place may continue to change. Additionally, recording, as near as possible, the exact place of an event in the past gives a starting point for searching for the current location of a record of the event. Recording the current designation of the place where the event occurred obscures the historic reality also ignores the need to provide a path to finding the location of historical records. We cannot assume that historical records for an event in the past will still be located in the modern-day jurisdiction of the event.

In order to provide a framework for standardization for the recordation of the location of historical events, it is necessary to determine a comprehensive methodology for recording such information in citations and database programs. In the past, genealogists relied on paper forms, these forms, in a real sense, dictated the specificity of events’ location information. Most of the

The basic problem with locations as it exists in the Family Tree can be illustrated by the following list of places taken from the birthplaces of twelve children in the same family born between 1780 and 1804 and listed as born in Virginia, Kentucky, and Indiana. You might note that Kentucky did not become a state until June 1, 1792. I should also mention that Nicholas County, Kentucky was not created until June 1, 1800. Here is the list.

· Birth abt 1780 Lincoln, Kentucky, United States

· Birth 1787 Of,,,Ky

· Birth abt 1787 of Nicholas Co., Ky.

· Birth about 1789 Kentucky District, Nicholas, Virginia, United States

· Birth 1791 Carlisle, Nicholas, Kentucky, United States

· Birth 1793 Ky

· Birth 1795 Of,,,Ky

· Birth 1797 Of,,,Ky

· Birth 1799 Of,,,Ky

· Birth abt 1801 of Nicholas Co., Ky.

· Birth 1802 Nicholas, Kentucky

· Birth abt 1804 of Nicholas, Ky.

I should also mention that there are no sources listed showing any birth records for any one of these children.

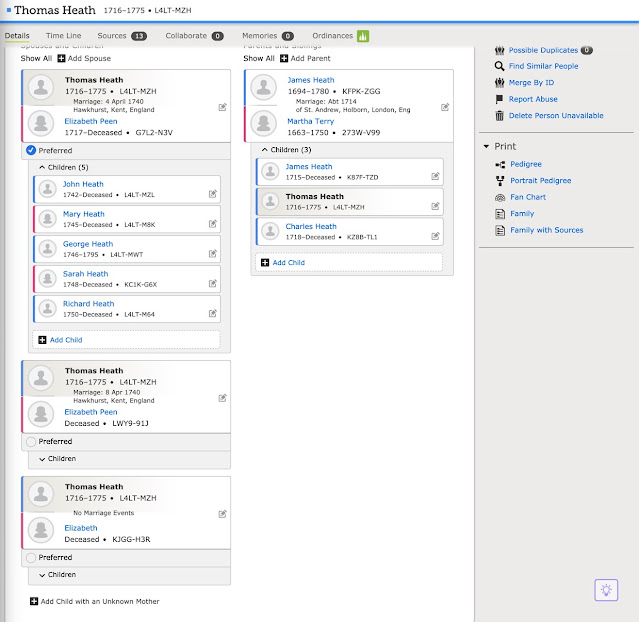

The FamilySearch.org website has one general blank space for entering location information about each specific event. FamilySearch has apparently decided not to try to segment location information into separate distinct categories by providing more than one blank space for data entry. Here is a screenshot of a typical individual data entry form from the FamilySearch Family Tree:

Unlike a paper form, the size of the space for entering a place does not limit the length of the entry. If you begin typing a location in the space provided, you will get a dropdown list of standardized locations associated with specific time periods. However, the user’s choice of which location to select depends entirely on the user’s understanding of the location’s history and how the location was characterized during each phase of that history. There are no prompts or instructions guiding the novice user in making a decision as to which designation applies. There is also a measure of confusion when, as happens from time to time, the “standard” locations offered by the program do not correctly match the actual historical location. Additionally, FamilySearch has provided a way by which the user can add his or her own “standard” location. Some of these suggested standard locations are then adopted, over time, into the standard database. This is most frequently done with cemetery locations.

In addition, some of the standard locations are artificially contrived. For example, pre-Revolutionary War locations in what is now the United States are often classified by the standardization system as “British Colonial America.” Here is an example of that designation from the FamilySearch Family Tree:

This characterization of “British Colonial America” is not a place or a level of jurisdiction. It can also be confusing if applied to the area of the North American continent outside of British jurisdiction such as Florida before 1821 which was under the control of Spain, France, or Great Britain depending on the particular time period involved. I have yet to see designations such as French Colonial America and Spanish Colonial America although they may exist. These additional designations, if applied, would also be misleading and inappropriate.

Here is an example from the Family Tree of a standardization suggestion for a location in Utah or Arizona showing some of the different choices. In each case, you can see that FamilySearch has also added a time period assumedly corresponding to the time the particular designation was in effect. The dropdown menu scrolls to let the user see more options.

The following screenshot from the FamilySearch.org Family Tree was chosen to address the issue of locations that are often identified as located in the “United States” before 1776. Such as this one:

So how do you identify a location such as the one illustrated above in Virginia? Omitting the reference to the United States would make the entry more accurate but how do you identify the fact that the Virginia Colony was part of the Kingdom of Great Britain beginning in 1707 and lasting until the traditional cut-off date of 1776.

Generally speaking, each location in any time period is associated with a layer of jurisdictions. A genealogical researcher cannot assume that records created in the Virginia Colony prior to 1776 did not make their way to England. If the goal is to provide an accurate place where to begin a record search, as I explained above, then accurately recording the way the place was designated at the time of the event provides the most assistance.

All the jurisdictional entities for historical locations have a distinct date of origin unless they date back to when records are not available at all. It is important to carefully examine each level of designation, even if there is a list of “suggested” standard place names and the associated dates. A good example of why this is necessary is illustrated by the second standard option listed above which refers to “Augusta, Hampshire, Virginia, United States.” The problem here is that both Augusta and Hampshire are counties. Augusta County was created in 1738. Hampshire County was created from Augusta and Frederick counties in 1754. So, if the event occurred in1755 in the area of Hampshire County, then it did not occur in Augusta County. However, the location information is more complicated than you would think especially if you only look at the suggested standard locations. Quoting from Wikipedia: Trinity Episcopal Church (Staunton, Virginia) concerning Augusta County:

Founded first as Augusta Parish Church in 1746. In 1747, the Reverend John Hindman became the first rector. This church, Augusta Parish Church, served as the only government of Augusta County until 1780 when the Parish Vestry was dissolved by legislative act. It is the oldest church in Staunton. In May 1781, the Virginia General Assembly fled Monticello ahead of advancing British troops, and landed in Staunton, where they set up the assembly in Augusta Parish Church, from June 7 to June 23 of that same year.

Currently, parts of the original Augusta County, following a number of changes as other counties were established, are located in West Virginia since their separation from Virginia on June 20, 1863. So where would the records be today from 1755? Answering that question may involve learning a lot of the local history. There is obviously really no way to standardize this place in Virginia from the list provided by FamilySearch. But assuming that the event took place in Augusta county, my correct interpretation of this location might be:

Augusta Parish, Virginia Colony, Kingdom of Great Britain

However, Augusta County came into existence as a fully organized county in 1745. It might be helpful to add the word “county” especially in situations where there is a town or city with the same name as the county.

Augusta Parish, Augusta County, Virginia Colony, Kingdom of Great Britain

FamilySearch consistently omits the word “county” from their location names.

Establishing standards and defining the location should reflect the correct jurisdictional locations but the discrete categories are essentially the same. In this case, three or four categories corresponding to most localities, the next level of jurisdiction, and subsequent levels can be adequately expressed in three or perhaps four levels. However, there is one more level of accuracy that should have been expressed by the research: the actual place the event occurred. Augusta County was originally a very large area and lost ground to Frederick County and Hampshire County (now in West Virginia) in 1754. Augusta County continued to lose land area to other counties and jurisdictions to as recently as 1994. See the Atlas of Historical County Boundaries from the Newberry Library.

As you can see from the example, attaching labels to the levels of jurisdiction is problematic. If you had the following very common set of labels (i.e. blank spaces in which to add a place) how would you choose to enter the information?

City, County, State, Country

By the way, it is very likely that the person who originally entered the information was completely ignorant of the historical changes and since, in this case, the person in the FamilySearch Family Tree has no source citations but there is a note that the date and place originated from an application for membership in the Sons of the American Revolution. Could this applicant have actually found a birth date and place?

If I do a search in the FamilySearch Catalog for “United States, Virginia, Augusta,” I will see the following:

These are the categories of records available for Augusta County, Virginia in the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah. If you look at this page, you will see a further link to “Places within United States, Virginia, Augusta.” Clicking on that link will give you a list of cities or towns in the county. Here is a screenshot of the list.

Since the researcher in the example above designated only the county, unless a subsequent researcher finds a more specific location, the subsequent researcher will have to search every one of the records for each of these cities or towns. Although the researcher above had a “birth date” since there was no reference to a source, the subsequent researcher would be forced to determine if a birth record actually existed.

A quick look at the list of available vital records for Augusta County shows that the earliest birth records date from around 1853, nearly a hundred years after the date shown above for the birth. What about Church records? There are baptismal records from 1740 and some church records from as early as 1741 but assuming that the subsequent researcher could not find the records immediately by searching on FamilySearch, a full research effort could take a very long time when all the other possible locations for the record are considered. This is a very common example of why a specific location for an event is not only helpful, but necessary.