Genealogical Society of Utah. Lessons in Genealogy. Salt Lake City, Utah: The Genealogical Society of Utah, 1915, Page 53.

Monday, July 27, 2020

Will computers ever change genealogical methodology?

Genealogical Society of Utah. Lessons in Genealogy. Salt Lake City, Utah: The Genealogical Society of Utah, 1915, Page 53.

Saturday, July 25, 2020

The Sixth Generation Barrier

Thursday, July 23, 2020

Getting the most out of historical records

Wednesday, July 22, 2020

Comments on truth in genealogy

The basic idea of the correspondence theory is that what we believe or say is true if it corresponds to the way things actually are – to the facts.

9 We believe all that God has revealed, all that He does now reveal, and we believe that He will yet reveal many great and important things pertaining to the Kingdom of God.

|

| http://genealogy.az.gov/azbirth/448/4480980.pdf |

Tuesday, July 21, 2020

How Many Records in the World have been digitized? A Cautionary Tale

NARA keeps only those Federal records that are judged to have continuing value—about 2 to 5 percent of those generated in any given year. By now, they add up to a formidable number, diverse in form as well as in content. There are approximately 10 billion pages of textual records; 12 million maps, charts, and architectural and engineering drawings; 25 million still photographs and graphics; 24 million aerial photographs; 300,000 reels of motion picture film; 400,000 video and sound recordings; and 133 terabytes of electronic data. All of these materials are preserved because they are important to the workings of Government, have long-term research worth, or provide information of value to citizens.

Monday, July 20, 2020

Plumbing the Depths of the FamilySearch Catalog

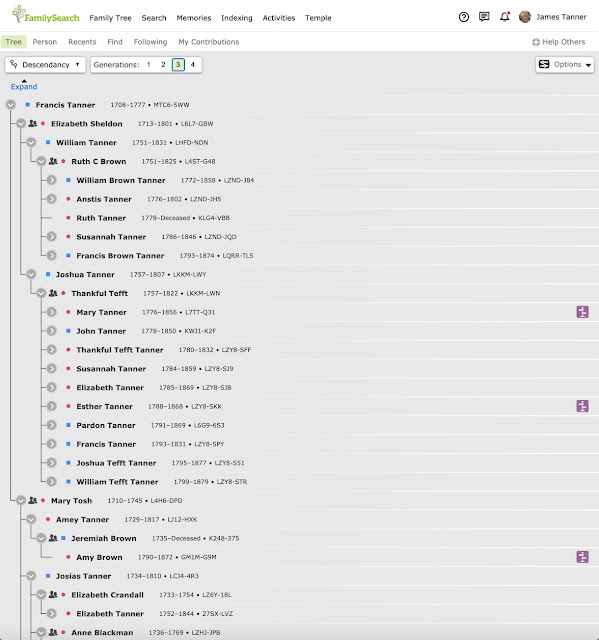

- Digital images published in FamilySearch's Historic Collections online 1.43 Billion

- Digital Images published only in the FamilySearch Catalog online 1.8 Billion

- Number of searchable historic record collections online 2,845 Collections

- Number of searchable records 5.07 Billion

- Number of digital books 489k

Saturday, July 18, 2020

Where is British Colonial America? What do we mean by standardization?

|

| Fantasy World |

Using standard formats for dates and places in Family Tree improves the accuracy and searchability of the information you enter.

The database of standard places is not yet complete. The standards will improve over time.

Friday, July 17, 2020

DNA Helps to Solve an Ancestral Mystery

Wednesday, July 15, 2020

What's Happening with Genealogically Oriented Publications?

Saturday, July 11, 2020

A New Rule of Genealogy Discovered: Number Thirteen

- Rule One: When the baby was born, the mother was there.

- Rule Two: Absence of an obituary or death record does not mean the person is still alive.

- Rule Three: Every person who ever lived has a unique birth order and a unique set of biological parents.

- Rule Four: There are always more records.

- Rule Five: You cannot get blood out of a turnip.

- Rule Six: Records move.

- Rule Seven: Water and genealogical information flow downhill

- Rule Eight: Everything in genealogy is connected (butterfly)

- Rule Nine: There are patterns everywhere

- Rule Ten: Read the fine print

- Rule Eleven: Even a perfect fit can be wrong

- Rule Twelve: The end is always there

Friday, July 10, 2020

Beginning the Mayflower Quest Part Nine: The persistence of birth

|

| Mayflower II in the Plymouth, Massachusetts Harbor (my photo) |

Richard Warren KXML-7XC, a Mayflower passenger is another of my Revolving Door Ancestors. Here are some quotes about his birth.

Richard Warren's English origins and ancestry have been the subject of much speculation, and countless different ancestries have been published for him, without a shred of evidence to support them. http://mayflowerhistory.com/warren

The Richard Warren Silver Book, Mayflower families through five generations. descendants of the Pilgrims who landed at Plymouth, Mass. December 1620 Volume eighteen, part III, Volume eighteen, part III reads that Mourt's Relation states he was from London and that “This statement that he was from London is all we know about the origin of Richard Warren despite considerable research to learn more.” See Mayflower families through five generations. descendants of the Pilgrims who landed at Plymouth, Mass. December 1620 Volume eighteen, part III, Volume eighteen, part III. 2001.

See previous posts

Introduction: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2020/06/popularity-on-familysearch-family-tree.html

Part One: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2020/06/beginning-mayflower-quest-evaluating.html

Part Two: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2020/06/beginning-mayflower-quest-part-two.html

Part Three: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2020/07/beginning-mayflower-quest-part-three.html

Part Four: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2020/07/beginning-mayflower-quest-part-fourth.html

Part Five: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2020/07/beginning-mayflower-quest-part-five.html

Thursday, July 9, 2020

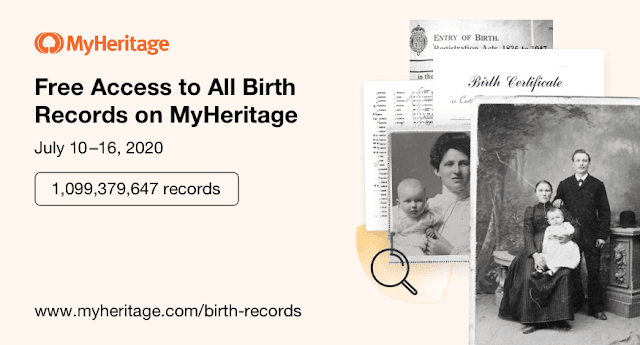

Free Access to All Birth Records on MyHeritage

We’re happy to announce that we’ll be offering free access to all birth records on MyHeritage from July 10–16, 2020!MyHeritage boasts a vast treasure trove of 104 birth record collections, containing more than 1 billion records from all over the world. Birth records are a perfect place to start when researching your ancestors, offering an important glimpse into the moment when their lives began. Where did it happen? On what date, and at what time? Who was present for the birth, and who registered it? You might learn the answers to these questions from a birth record.

Normally, most of these records are fully accessible only to paid subscribers of MyHeritage, but as of July 10 and ending July 16, you’ll be able to access them freely even if you’re not a paid subscriber. This is an excellent opportunity for users who have wanted to access birth records on MyHeritage but haven’t wanted to commit to a subscription.

Beginning the Mayflower Quest Part Eight: Working with the weekly Reports

|

| Pilgrim Memorial State Park in Plymouth, Massachusetts |

There are currently 188 people watching Francis Cooke LZ2F-MM7 and 544 past contributors. How many of them do you think agree on every detail of his life and his family? Once you have taken on a project to work with a "Revolving Door" ancestor or family, you probably will want to check your FamilySearch Family Tree messages and look at any particularly "changeable" ancestors more frequently than once a week. Getting upset or mad about the changes is nonproductive. Anyway, before you get mad, you should make absolutely sure that anything you do is supported by sources (in the plural) and makes sense. Make use of the Recents menu on the Family Tree to quickly review any changes. If you made the last change, then your name should be at the top of the list of Latest Changes.

Here is an example of a weekly report.

As you can see from the heading, this report includes changes to 15 people and has a total of 74 changes. As I pointed out previously with an early report, Most of those changes pertain to one individual, in my case, Francis Cooke LZ2F-MM7.

You can review a report like this in just a few minutes if you don't have a Revolving Door ancestor (or more) on the list. In the case of Francis Cooke, the changes can be fairly complex. I am guessing but after reviewing thousands of changes over the years, I believe that only about 10% or less have a supporting source. The most frequent changes almost never have a source listed supporting the change. This particular list took me just a few minutes to review. Except for Francis Cooke, the rest of the changes were adding sources or similar activities.

If those people who were correcting the incorrect changes would have taken one more step, then the number of changes would have gone down by now. As I have noted in previous posts. it is important to explain to the person making the wrong change why their change was wrong. Usually, a short answer is not enough. I compile a set of "standard" responses to the most common changes and have them in a program or file that I can access easily. I copy the response and use it as the reason for me changing the error and also send a copy of the reason to the person who made the improper change. I only very occasionally get any response back but I notice that the person seldom makes the same change again.

What about those people out there who are certain that their information is correct and continue to change it back? I have found the sending longer and longer explanations usually helps but sometimes you just have to last them out and keep correcting the entry until they get tired of the process. I never get tired of the process. With an ancestor such as Francis Cooke, you cannot expect to see any results from your efforts for months or even years of work. But slowly, the old PAF files and GEDCOM files are exhausted and no one has anymore basis for taking an interest in your and their ancestor.

It certainly helps if there are other relatives who are willing to assist in the process but don't count on that happening. If you do find someone correcting bad entries and supporting changes with valid sources, it is a good idea to send them a thank you note.

It is extremely important that you do all the research and know more than you think is even reasonable about the people you support in this way. Don't be part of the problem. By the way, do not ever use a Mayflower Society Application as a supporting source for a change. Always go to original contemporary, if possible, sources.

See previous posts

Introduction: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2020/06/popularity-on-familysearch-family-tree.html

Part One: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2020/06/beginning-mayflower-quest-evaluating.html

Part Two: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2020/06/beginning-mayflower-quest-part-two.html

Part Three: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2020/07/beginning-mayflower-quest-part-three.html

Part Four: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2020/07/beginning-mayflower-quest-part-fourth.html

Part Five: https://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2020/07/beginning-mayflower-quest-part-five.html