Before we can improve our own genealogical research skills or teach other, we need to have a basic understanding of the research process. Next, we need an understanding of how that research process is implemented using online sources. Finally, we need to move beyond a theoretical knowledge of the subject and practice the process until we obtain the skills necessary for mastery. To start on this path, the first step is understanding research. What is research and more particularly, what is genealogical research?

During my life, I have been involved in a lot of different types of research. For more than forty years, I did "legal research." This particular type of activity was mis-named since there was little or no actual research involved. What passed as research in the legal community was searching for cases that supported your client's position in a lawsuit or potential lawsuit. This was based on the concept of stare decisis, inherited from the English Common Law. The idea is that when a judge in a court of record makes a written decision, the opinion expressed in the decision becomes binding on judges making subsequent similar decisions. So, the job of the legal researcher is to find support for his or her case. One limitation is that ethically, the legal researcher cannot ignore or fail to call to the Court's attention cases that oppose the one being researched.

This is essentially the antithesis of what we are talking about when we use the term "genealogical research." In addition, genealogical research differs substantially from scientific research despite repeated attempts in the genealogical writings to claims of using the scientific method or research in genealogy. Simply using the same terms to refer to an activity does not make them the same. Legal research is not the same as scientific research and scientific research is definitely not the same as genealogical research. The similarities are sometimes emphasized at the expense of twisting the terminology into submission to a particular opinion.

One thing the different types of activities collectively referred to as "research" have in common is the idea of searching. The searching part of research is the methodology used by the people participating in the activity. The activity is defined by its objective. In other words, the type of research you are doing is determined by what you are looking for. In the legal profession, as in every other type of activity branded as research, there are extremely varying degrees of ability and success as researchers.

Another concept common to all types of research is the idea of moving from the known to the unknown. However, the key difference here is the quality of the unknown. In Law, the unknown is merely a collection of relevant cases. In our modern age, nearly every possible legal authority is exhaustively reproduced online. A complete transcript of every single case ever recorded is available to be searched on huge database programs such as West Law. The amount of information in these huge online databases is staggering. It has been some time, but I have pointed out in the past, that a West Law search can have valuable genealogical content.

This idea of moving from the known to the unknown is really one of the very few things the different types of activities called research have in common. Stripped down to their absolute essentials, here are the objectives of the three types of research I have mentioned so far:

Legal Research - the objective of legal research is to find case law (wording in certain cases) that supports the claims made by an attorney's client in a legal dispute.

Scientific Research - the objective of scientific research is to discover the laws that govern the physical world and then understand how those laws function in order to predict how the laws apply to our physical existence.

Genealogical or historical research -- the objective of genealogical research is to gather specific information about specific individuals from historical records and organize and preserve such information.

All types of research are by their nature repetitious activities. The research does essentially the same thing over and over again, until the objective is obtained. Presently, legal research deals with a finite body of records that are growing each day as new law cases are decided, new laws passed and new regulations made. But every last case can be completely searched using the powerful online tools available. Legal research is nothing more or less than citing law cases. There are very, very few surprises, only innovative new arguments. But there is enough new law all the time to make the process mildly interesting.

Since scientific research deals with the unknown, unrecorded and untested, it is substantially different. An experienced lawyer almost always knows enough about his or her own area of the law to accurately predict what the case law will say on any given controversy. Scientists seldom know anything about the objects of their research and new discoveries are constantly overturning established theories and assumptions.

Genealogical research consists of searching historical documents for clues and information about individuals and families. It differs from legal research in that the corpus of the research is scattered around the world and is far from being entirely known and available for easy access. Even the largest genealogical database programs have only a small percentage of all the available records. In this, genealogical research is much, much more interesting than legal research. In genealogy, there is always more information to discover. In Law, it is all cut and dried. The cases are all there and the only differences between attorneys are their individual abilities to find those cases and then exploit them.

From my standpoint of doing both legal research and genealogical research for many, many years, I can say absolutely, they have little in common other than the idea of searching records.

So, now we do have some general things we can say about all of the differing types of research.

1. They all involve searching.

2. They all involve moving from the known to the unknown.

3. They all involve making a record of what is found in some fashion.

4. They each require a set of learned skills that vary according to the experience and ability of the researcher.

In some ways, legal research and genealogical research have more in common than scientific research. There is one part of the scientific research process however, that is similar. The scientist has to do a historical review to see what other scientists have already discovered about the subject under investigation. This review or survey is also a common activity, but very limited in scope in the scientific community and not the objective of the research at all. Whereas, in both law and genealogy, seeing what has already been recorded is the objective of the search.

So, genealogical research is a structured activity aimed at discovering the content of records and documents scattered around the world. It is distinctive from other activities called research in its objectives and the corpus of its search efforts. But it is also fundamentally different than research in the legal and scientific fields.

Stay tuned for Part Two.

Sunday, May 18, 2014

Saturday, May 17, 2014

Genealogy vs. The Youth

One of recurring themes of today's genealogical community is the idea of involving the youth in genealogy. Whether done under the guise of family history or some other activity, the goal is to get the youth interested in doing genealogical research. However, most of the programs I have seen are aimed more at motivation than acquiring the skills necessary to actually participate in genealogical research. In working with thousands of patrons at the Mesa FamilySearch Library over the past years, including many much younger than I am, I have found one of the major limiting factors for a successful genealogical experience is a lack of research skills. Motivation without knowing the methodology and without the skills to implement that methodology, leads to frustration.

At this point in my discussions of this subject, someone usually starts to contradict me with a story about some phenomenal youthful researcher who has found thousands of names. As they sometimes say, the exception proves the rule. There are people with these skills, old and young, there just aren't that many of them around.

This issue does not apply only to youth, but there are special challenges that usually remain unaddressed in the programs aimed at youthful potential genealogists. Whatever you call it, genealogy is a research intensive activity. Research skills are not easily acquired and are lacking in many young people today, even those who are already attending major universities. Back in 2011, a series of studies were conducted at Illinois Wesleyan, DePaul University, and Northeastern Illinois University, and the University of Illinois’s Chicago and Springfield campuses. The study was called ERIAL or Ethnographic Research in Illinois Academic Libraries project. A report about the project entitled, "What Students Don't Know" stated,

One egregious example of the lack of research awareness is the commonly held belief that you can do "research" in an online family tree program. I find people searching through FamilySearch.org Family Tree and other online family tree programs that actually believe they are "researching their family." Unfortunately, the disconnect is so large that genealogists are not even aware of its existence. So how do you teach research skills? Yes, it is a learned skill and yes, it can be taught and learned.

In my next post I will discuss some of the ways we can enhance our own research skills and how those skills can be taught to others. If you don't thing this applies to you, either as a researcher or a teacher, then you need to read the article.

At this point in my discussions of this subject, someone usually starts to contradict me with a story about some phenomenal youthful researcher who has found thousands of names. As they sometimes say, the exception proves the rule. There are people with these skills, old and young, there just aren't that many of them around.

This issue does not apply only to youth, but there are special challenges that usually remain unaddressed in the programs aimed at youthful potential genealogists. Whatever you call it, genealogy is a research intensive activity. Research skills are not easily acquired and are lacking in many young people today, even those who are already attending major universities. Back in 2011, a series of studies were conducted at Illinois Wesleyan, DePaul University, and Northeastern Illinois University, and the University of Illinois’s Chicago and Springfield campuses. The study was called ERIAL or Ethnographic Research in Illinois Academic Libraries project. A report about the project entitled, "What Students Don't Know" stated,

At Illinois Wesleyan University, “The majority of students -- of all levels -- exhibited significant difficulties that ranged across nearly every aspect of the search process,” according to researchers there. They tended to overuse Google and misuse scholarly databases. They preferred simple database searches to other methods of discovery, but generally exhibited “a lack of understanding of search logic” that often foiled their attempts to find good sources.Essentially, these students would have been considered to be "Internet saavy." The study was cited as exploding the "Myth of the Digital Native." The report states,

Only seven out of 30 students whom anthropologists observed at Illinois Wesleyan “conducted what a librarian might consider a reasonably well-executed search,” wrote Duke and Andrew Asher, an anthropology professor at Bucknell University, whom the Illinois consortium called in to lead the project.

Throughout the interviews, students mentioned Google 115 times -- more than twice as many times as any other database. The prevalence of Google in student research is well-documented, but the Illinois researchers found something they did not expect: students were not very good at using Google. They were basically clueless about the logic underlying how the search engine organizes and displays its results. Consequently, the students did not know how to build a search that would return good sources. (For instance, limiting a search to news articles, or querying specific databases such as Google Book Search or Google Scholar.)As I stated above, this problem does not apply only to the youth. As I deal with genealogists and potential genealogists, young and old, I find that there is a tremendous need for education in basic research skills. I am not writing about basic genealogy skills, I am writing about basic computer-based research skills. The article goes on to state,

Duke and Asher said they were surprised by “the extent to which students appeared to lack even some of the most basic information literacy skills that we assumed they would have mastered in high school.” Even students who were high achievers in high school suffered from these deficiencies, Asher told Inside Higher Ed in an interview.

In other words: Today’s college students might have grown up with the language of the information age, but they do not necessarily know the grammar.The rest of the article goes on to describe the deficiencies observed. The students failed to ask the librarians for help and viewed them as "glorified ushers." Sometimes, that is what I think the younger patrons at the Mesa FamilySearch Library think about the missionaries and volunteers. The article also notes that whenever this subject is addressed "people get their backs up." I have found exactly the same response whenever I bring up this same subject.

One egregious example of the lack of research awareness is the commonly held belief that you can do "research" in an online family tree program. I find people searching through FamilySearch.org Family Tree and other online family tree programs that actually believe they are "researching their family." Unfortunately, the disconnect is so large that genealogists are not even aware of its existence. So how do you teach research skills? Yes, it is a learned skill and yes, it can be taught and learned.

In my next post I will discuss some of the ways we can enhance our own research skills and how those skills can be taught to others. If you don't thing this applies to you, either as a researcher or a teacher, then you need to read the article.

What I learned from the Digital Map List

In my last blog post, I got involved in making a list of online sources for digitized maps. When I sit down to help someone with their research, one of the very first things I do is check the locations mentioned on a map, usually Google Maps program. Since I am very visual this helps me get oriented as to what and where the events occurred that might give rise to more sources. But a more fundamental reason is that the people I help seldom have the vaguest clue about where all this stuff they have about their ancestors occurred. Knowledge of the geography is one factor that separates a knowledgeable researcher from one that has not yet understood the concept of genealogical research. If the researcher lacks geographic orientation, I can very quickly determine that they also lack understanding of the types of records that will help them further their research.

So my motivation was somewhat selfish in that I wanted to see whether or not my claim was true that digitized maps were extensively available. There is no doubt that huge map collections exist, my question was to what extent are these available online. For example, the Library of Congress describes its collection as follows:

Back to maps, so why would I make a hard-to-substantiate claim that almost all the maps necessary for research had been digitized when the Library of Congress clearly states that only a "small fraction" have been digitized? Why the discrepancy? Well, from one standpoint, the United States Government is one of the poorest examples of making their records available through digitization. Some single states have more digitized and freely available records than the entire U.S. Government has yet done so. In fact, the Library of Congress has only 12,961 digitized maps online. Whoa. Why that tiny number? How can they possibly use the "copyright excuse" for that shrinky little smidgen of maps? Good question.

But here is the crux of the matter, for genealogy maps are maps are maps.

For an example of what I mean is simply illustrated. Here is a map of Arizona from the Library of Congress. Oh, by the way, the Library of Congress has only 40 maps of Arizona online. I had more than that sitting in my library and boxes of maps, until I gave the box to our local library. Anyway, here is an example:

This particular map is R.P. Kelley's map of the territory of Arizona, created or published in St. Louis, Missouri by Theodore Schrader, 1860. Now, if you search for this same map in WorldCat.org, you find that at least10 other entities, universities, libraries, historical societies etc., have copies of the same map, not including the large online map websites. Here is a link to a website illustrating 10 old maps with the same information as this example.

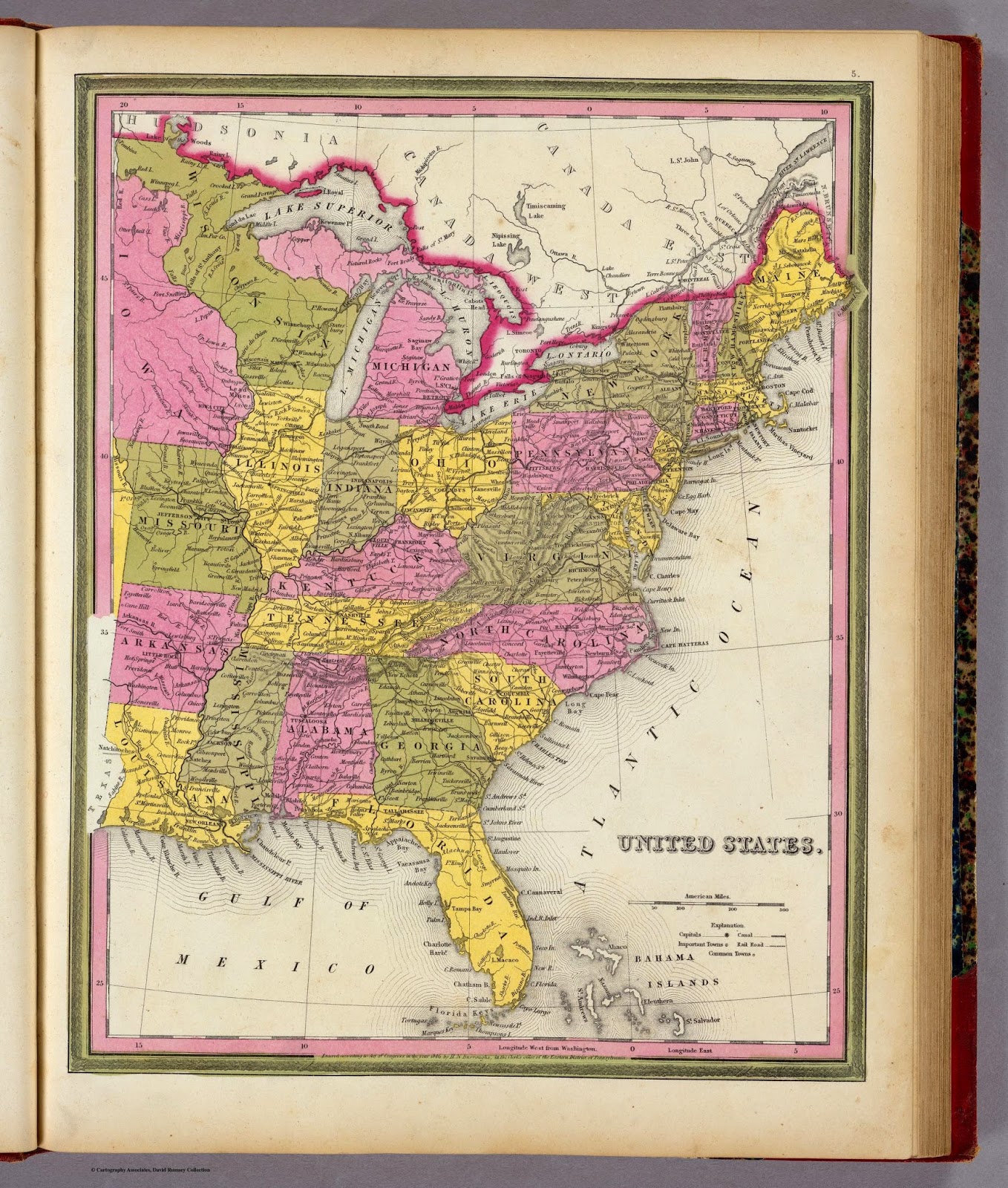

It is also possible to find another map from exactly the same year. Here is an example from the David Rumsey Map Collection.

USGS Topographical Maps which cover the entire United States and the online index to all of that provided by the U.S. Board of Geographic Names. Thus we can find places that are no longer on current maps.

So the question evolves into whether or not you are interested in historic maps per se, or if you are actually looking for a location. Like I mentioned the Library of Congress is not such a good place to look for maps online. I would suggest OldMapsOnline.org as a better source. But the point here is and the point that was reinforced by my exercise in making a list of online sites, that there are more maps online than you have the patience to look at and finding a location using satellite maps, Google Maps, the USGS and the Geographic Names Board makes the job possible even if you can't find the place on a map.

So my motivation was somewhat selfish in that I wanted to see whether or not my claim was true that digitized maps were extensively available. There is no doubt that huge map collections exist, my question was to what extent are these available online. For example, the Library of Congress describes its collection as follows:

The Geography and Map Division (G&M) has custody of the largest and most comprehensive cartographic collection in the world with collections numbering over 5.5 million maps, 80,000 atlases, 6,000 reference works, over 500 globes and globe gores, 3,000 raised relief models, and a large number of cartographic materials in other formats, including over 38,000 CDs/DVDs. The online Map Collections represents only a small fraction that have been converted to digital form. These images were created from maps and atlases and, in general, are restricted to items that are in public domain, meaning those which are not covered by copyright.So, one thing I learned is that access to some types of information is measurably impeded by copyright restrictions. But my response to that point, from a genealogical perspective, was that many of the maps under copyright deal with current conditions. What about the historical maps? These would seem to be the ones most useful. Anyway, you can't copyright a list of place names so there should be a way to find almost any place even if the maps were locked up by copyright (I was going to use the phrase silly, ridiculous, out-dated, bureaucratic, oppressive, impractical, copyright, but thought better of it). Here, of course, I had to use a measure of self-control to avoid going off on a tangent about why all those terms apply to our current copyright law, but that is another post for another time.

Back to maps, so why would I make a hard-to-substantiate claim that almost all the maps necessary for research had been digitized when the Library of Congress clearly states that only a "small fraction" have been digitized? Why the discrepancy? Well, from one standpoint, the United States Government is one of the poorest examples of making their records available through digitization. Some single states have more digitized and freely available records than the entire U.S. Government has yet done so. In fact, the Library of Congress has only 12,961 digitized maps online. Whoa. Why that tiny number? How can they possibly use the "copyright excuse" for that shrinky little smidgen of maps? Good question.

But here is the crux of the matter, for genealogy maps are maps are maps.

For an example of what I mean is simply illustrated. Here is a map of Arizona from the Library of Congress. Oh, by the way, the Library of Congress has only 40 maps of Arizona online. I had more than that sitting in my library and boxes of maps, until I gave the box to our local library. Anyway, here is an example:

This particular map is R.P. Kelley's map of the territory of Arizona, created or published in St. Louis, Missouri by Theodore Schrader, 1860. Now, if you search for this same map in WorldCat.org, you find that at least10 other entities, universities, libraries, historical societies etc., have copies of the same map, not including the large online map websites. Here is a link to a website illustrating 10 old maps with the same information as this example.

It is also possible to find another map from exactly the same year. Here is an example from the David Rumsey Map Collection.

USGS Topographical Maps which cover the entire United States and the online index to all of that provided by the U.S. Board of Geographic Names. Thus we can find places that are no longer on current maps.

So the question evolves into whether or not you are interested in historic maps per se, or if you are actually looking for a location. Like I mentioned the Library of Congress is not such a good place to look for maps online. I would suggest OldMapsOnline.org as a better source. But the point here is and the point that was reinforced by my exercise in making a list of online sites, that there are more maps online than you have the patience to look at and finding a location using satellite maps, Google Maps, the USGS and the Geographic Names Board makes the job possible even if you can't find the place on a map.

Friday, May 16, 2014

Online Digital Map Collections by State

The reason for listing all these digitized map links is twofold; first to produce the links and provide the information, second to illustrate the fact that searching online can be an endlessly productive activity. I am always skeptical of anyone's claims that they have searched all the available records. Every time I returned to this project, I found more links and no, I did not go to any one source and simply copy someone's work. In some cases, I incorporated part of the list from a particular website, but I did not find anyplace where all these websites were listed. I also intend to incorporate all this information in the FamilySearch.org Research Wiki over the next few weeks (months?).

The attention of the genealogical community has been focused on maps available through huge online repositories and portals. Some of the largest of these include the following:

- OldMapsOnline.org

- The David Rumsey Map Collection

- The Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection

- Maps: Scanned collections online from the British Library

- Trove.nla.gov.au Maps

- The New York Public Library

- The Library of Congress

- USGS Topographical Map Collections including historical topographical maps

- Western Waters Digital Library

- Michigan State University, Using Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps Online

- Ancestry.com

- Archive.org

- Digital Public Library of America

- United States Census Bureau State and County Map

- Historic Map Works

- Newberry Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

- University of Texas at Austin, Historical Maps Websites

- American Geographical Society - Digital Map Collection

- Ancient World Mapping Center - Maps for Students

- Digtal-Topo-Maps.com

- National Archives, Cartographic and Architectural Records

- Public Domain Sherpa, Public Domain Maps

- Olin and Uris Libraries, Cornell University, GIS Data and Maps, United State

- Index to Digital USGS 15 Minute Topographical Maps

- Map History, Images of early maps on the web

- DigitalStateArchives.com

- University of New Hampshire, Historic USGS Maps of New England and New York

- Rails and Trails, Historic Transportation Sources

- NationalAtlas.gov

- US Forest Service Maps

There are many, many more that could be listed. You can, of course, search any one or all of these large online collections for maps of the individual states of the United States and other places around the world. Please excuse any duplications in links. Sometimes, the link applied to more than one state and sometimes it was difficult to tell if the links went to the same website or not.

However, in the United States, it is important to note that there are also significant map collections in most states. The following is a listing of some of the map collections available for each state in the United States. I have included some of the larger collections. Please understand that this list is not exhaustive. You may find even more online locations by searching for "state name map collections." Of course, there are huge numbers of paper maps available in libraries and other repositories across the country, but many of those are merely copies of maps already digitized. Have a good time looking at and searching all these maps.

It is interesting to see that some states have extensive digital map collections and other have practically nothing online. In Arizona, for example, both the state universities have huge map collections but practically none of those are digitized or available online. This also reflects the condition of the rest of the state archives, some have huge collections online such as the State of Washington, others practically nothing. Also, some of these state collections contain maps from all over the United States and world.

Alabama

- University of Alabama Map Collection

- Alabama State Maps Collection

- Alabama Maps

- Alabama County Maps and Atlases

- Alabama Dept. of Transportation maps

- Alabama Genealogy: Maps

- Alabama Maps

- Alabama County Maps

- The History of the Black Belt

- Geologic and Geographic Setting

- Alabama maps, The Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, The University of Texas at Austin

- Panoramic Maps, 1847-1929

- Joe's Alabama Road History

- Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

Alaska

American Samoa

Arizona

Arkansas

California

- California Historic Topographic Map Collection, California State University, Chico

- California Geological Survey, Geologic Maps

- Maps of California

- Historical Maps of Southern California

- University of California, Berkeley Earth Sciences and Map Library

- Los Angeles County Historical Topographical Maps

- SDAG Historical Topographical Maps, San Diego County

- UCLA Library, Digital Collections

- Online Archive of California

- Humboldt State University Library, Digital Spatial Data

- Stanford University, Digital Collections, Glen McLaughlin Map Collection

- Los Angeles Public Library, Map Collection

- San Fernando Valley History Digital Library

- Stanford University, Branner Earth Sciences Library and Map Collections

- Cal-Atlas Geospatial Clearinghouse

- Historic topographic maps of California, U.C. Berkeley

- Digital Atlas of California

- Los Angeles County Historical Topographic Maps

- Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority

- Los Angeles and the Problem of Urban Historical Knowledge: Maps

- Official Los Angeles city web site

- Los Angeles County Office of the Assessor

- Navigate LA

Colorado

- Colorado BLM GIS/Mapping Science

- Colorado Colorado Atlas of Panoramic Aerial Images

- Maps of Colorado

- Colorado State University Libraries, Digital Collections

- Colorado Virtual Library

- University of Colorado, Digital Library

- University of Colorado, Boulder, Building Colorado Story by Story: The Sanborn Fire Insurance Map Collection

- Western Waters Digital Library, Digital Collections of Colorado

- Denver Public Library, Western History and Genealogy

- University of Northern Colorado, The Atlas of Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

District of Columbia

Florida

- Florida Data Directory

- Florida Department of Environmental Protection

- University of South Florida Libraries, Digital Collections

- Maps of Florida

- University of Florida, Digital Collections

- Florida Electronic Library, Florida Maps Collection

- State University of Florida, Publication of Archival Library and Museum Materials

- Digital Library of the Caribbean

- University of Central Florida, Florida Digital Collections

- Florida International University, Digital Collections Center

- Jacksonville Public Library, Digital Library Collection

- Florida State Archives, Florida Memory Project

- University of Miami, Old Florida Maps

Georgia

- University of Georgia, Hargrett Rare Map Collection (not digitized)

- Digital Library of Georgia

- Georgia State University, University Library, Historical Atlanta Maps

- Guide to Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, Georgia State University

- Georgia Historical Society

- Maps of Georgia

- University of Georgia Rare Books and Manuscripts - Digital Collections (includes maps)

Guam

Hawaii

Idaho

- Idaho State Historical Society

- University of Idaho Library, Digital Initiatives

- University of Idaho Library, Maps

- Maps of Idaho

- Idaho State University, Department of Special Collections and University Archives

- Idaho Genealogical Society

- Boise State University, Idaho Research

- Brigham Young University, Idaho, David O. McKay Library, Maps

- IDGenWeb Project, Idaho Maps and Places

- University of Idaho and the Portneuf Library, The Idaho Map Room

- Idaho Commission for Libraries, FARRIT, Idaho History

Illinois

- Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Genealogy Online

- Historical Maps Online

- Homicide in Chicago 1870-1930, Northwestern University

- Illinois Harvest (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

- Illinois Historical Digitization Projects

- Illinois Periodicals Online

- Illinois State Archives Databases

- University Libraries, Ball State University, Digital Media Repository

- Maps of Illinois

- University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, University Library, Historical Maps Online

- Illinois Digital Archives, Maps

- Northwestern University Library, Our Road Trip Issue: Old Illinois Highway Maps and Cost of Gas

- University of Chicago Library, Archival and Manuscript Collections, Map Collection

- USGenWeb Project, Illinois Digital Map Library

Indiana

- Indiana University - Purdue University, Indianapolis, Historic Indiana Plat books

- Ball State University Digital Media Repository (Browse)

- Hoosier Heritage Digital Library

- Indiana Historical Society - Digital Image Collections

- Indiana Magazine of History Online Index

- Indiana-Related Datases & Indexes, Indiana State Library

- The Indiana Geographic Information Council

- Maps of Indiana

- Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Historic Indiana Maps

- Indiana University, Image Collections Online, Indiana Historic Maps

- Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana Digital Atlas Collection

- Indiana University, Indiana Spatial Data Portal

- Indiana Historical Society

- Indiana Commission on Public Records, Aerial Photographs and Historic Maps

- Indiana State Library, Map Collection

- Indiana Department of Transportation maps

- Indiana Map (IGIC)

- University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa Counties Historic Atlases

- Maps of Iowa

- University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa Maps Digital Collection

- Iowa Geographic Map Server

- Iowa City and Johnson County, Digital History Project

- University of Northern Iowa, Rod Library, Regional Geography: Iowa

- Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Aerial Photography

Kansas

- The Kansas Collection

- Territorial Kansas Online

- Maps of Kansas

- Wichita State University Libraries, Department of Special Collections, A Collection of Digitized Kansas Maps

- Kansas Historical Society, Maps

- Kansas Memory

- Kansas State University, Digital Collections

- Fort Hays State University, Forsyth Library Digital Collections

- Territorial Kansas

Kentucky

- Kentucky Digital Library

- Maps of Kentucky

- University of Louisville, Kentucky Maps

- Kentucky Historical Society, Maps and Atlases

- University of Kentucky Libraries, Historic Maps

- University of Kentucky Libraries, Special Collections Library

- Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Special Collections and Archives

- KyGeoportal

Louisiana

- LOUISiana Digital Library

- Maps of Louisiana

- Tulane University Digital Library

- Atlas: The Louisiana Statewide GIS

- New Orleans Public Library, Louisiana Map Collection

- Louisiana Digital Library

- Tulane University, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Digital Initiatives

- Louisiana State University, Special Collections, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections

Maine

- Maine Geological Survey

- Maine Geographic Information Systems

- Maine Memory Network

- Maps of Maine

- Maine State Archives

- Windows on Maine

- University of Maine System Libraries, Digital Collections

- Maine Historical Society, Brown Library

- Maine State Library, Map Web Resources

- University of Southern Maine, Osher Map Library

Maryland

- Maryland Digtal Cultural Heritage

- Maryland State Archives Museum and Outreach

- Maps of Maryland

- University of Maryland, Special Collections and University Archives, Maryland Map Collection

- Maryland Historical Society, Special Collections: Maps and Atlases

- Maryland State Archives

- Johns Hopkins University, Sheridan Libraries, Special Collections and Archives, Garrett Map Collection

Massachusetts

- Harvard University’s Map Collection. Early Massachusetts maps

- Boston Subsurface Project

- Boston Streets. Digitized historical atlas of the Boston Area. Tufts University

- Digital Commonwealth, Massachusetts Collections Online

- Maps of Massachusetts

- Northeast Massachusetts Digital Library

- Massachusetts Historical Society, Massachusetts Maps

- University of Massachusetts, Amherst Libraries, Massachusetts Maps

- Special Collections and Archives Historic Maps

Michigan

- The Making of Modern Michigan

- Maps of Michigan

- Northern Michigan University, Lydia M. Olson Library, Maps, Atlases and GIS

- Michigan State University Map Collection

- University of Michigan Map Library

- Michigan Department of Education, MeL Michigana, Digital Projects

- University of Michigan, Michigan County Histories and Atlases

- Michigan Historical Center, Seeking Michigan

- Archives of Michigan

- Statewide Search for Subdivision Plats

- Western Michigan University, Digitized Collections

- Farmington Community Library Local History and Genealogy Resources

Minnesota

- Minnesota Digital Library

- Maps of Minnesota

- Minnesota Historical Society, The Michael Fox Map Collection, Minnesota Maps

- University of Minnesota, John R. Borchert Map Library, Digitized Plat Maps and Atlases

- Minnesota Digital Library

- Minnesota Geospatial Information Office

- Minneapolis Historical Records and Property History

- The Itawamba Historical Society, Online Digital Archives

Mississippi

- Mississippi Digital Library

- Maps of Mississippi

- Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Historical Map Collection

- Mississippi Maps

- University of Southern Mississippi, Digital Collections

- University of Mississippi Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

- Mississippi State University, Special Collections

- USGenWeb Mississippi Digital Map Library

Missouri

- University of Missouri Library Systems, Digital Library

- Missouri Digital Heritage

- Maps of Missouri

- The Kansas City Public Library, Missouri Valley Special Collections, Maps

- University of Missouri, Kansas City, Libraries, Digital Collections

- Missouri History Museum

- Unreal City, Historic St. Louis Maps

- University of Missouri Libraries, Special Collections and Rare Books, Digital Collections and Exhibits

- The State Historical Society of Missouri

- Missouri State University, Digital Collections

- Washington University Digital Gateway

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

- New Jersey State Archives

- Maps of New Jersey

- Historical Maps of New Jersey, Rutgers University

- Rutgers University Libraries, Special Collections and University Archives

- Princeton Public Library, Genealogy

- Princeton University, Historic Maps Collection

- Trenton Free Public Library, Trentoniana Historic Map Collection

- New Bunswick Free Public Library, Local History and Genealogy

- Rutgers University, Maps of New Jersey

- Rutgers University, Cartography

New Mexico

New York

- Hudson River Valley Heritage

- New York State Library

- Maps of New York

- Syracuse University Digital Collections

- USMA Library, Digital Collections

- New York Public Library, Digital Gallery Historic Map Guide

- New York Public Library, Open Access Maps

- New York State Library Selected Digital Historical Documents

- State University of New York at Stony Brook, New York State Historical Maps

- University of Albany, MapNY

- New York State Map Pathfinder

- New York University Libraries, New York City, Maps and Atlases

North Carolina

- North Carolina Digital Heritage

- North Carolina State Archives

- Eastern North Carolina Digital Library

- ECHO

- Maps of North Carolina

- North Carolina State University, Historical Data and Maps

- State Archives of North Carolina, Digital Collections and Publications

- North Carolina Maps

- North Carolina State University Libraries, Historical Data and Maps

- University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Online Collections

- DigtalNC

- East Carolina University, Eastern North Carolina Digital Library

- Forsyth County Public Library, North Carolina Room

- Davidson County, North Carolina, Maps

- Craven County Digital History Exhibit

- North Carolina Geological Survey, Maps and aerial photographs

- NC.gov

- Duke University, Maps

North Dakota

Northern Marianas Islands

Ohio

- Cleveland Digital Library

- Maps of Ohio

- Cleveland Memory Project

- The Southeastern Ohio Digital Shoebox Project

- Greater Cincinnati Memory Project

- Ohio Historical Society

- State Library of Ohio Digital and Special Collections

- Ohio State University Libraries, Maps

- USGenWeb, Ohio Digital Map Library

- The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, Virtual Library, Digital Maps

- Ohio University Libraries, Digital Collections

- Ohio Department of Transportation, Maps Resource Page

- Ohio Memory

- Rails and Trails, Historic Transportation Maps

- Toledo's Attic

- Miami University Libraries, Digital Collections

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Puerto Rico

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

- University of Houston, Digital History

- Maps of Texas

- University of Texas Libraries, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection

- Texas Map Society

- University of North Texas, Libraries, Portal to Texas History

- Texas State Historical Association

- Stephen F. Austin State University, Ralph W. Steen Library, Digital Archives and Collections

- University of Texas, Arlington, Digital Collections and Exhibits

- Texas A and M University Libraries, Digital Library

- Texas Tech University Libraries, Digital Collections

- Baylor University, Texas Collection, Maps

- Texas State University, Collections and Archives

Utah

- Pioneer, Utah's Online Library

- Maps of Utah

- Utah Digital Map Library

- Brigham Young University, Harold B. Lee Library, Collections

- Utah State University Digital Collections

- University of Utah, J. Willard Marriott Library, Sanborn Insurance Maps

- University of Utah, Digital Library

- Southern Utah University, Gerald R. Sherratt Library, Special Collections, Digital Archives

- Weber State University, Digital Collections

Vermont

Virginia

Virgin Islands

Washington

- Washington State University, Manuscripts, Archives and Special Collections, Historic Map Collection

- Maps of Washington

- Washington State Library, Maps

- Legacy Washington, Historic Maps

- Washington State University, Early Washington Maps

- University of Washington, Libraries, Map Collection and Cartographic Information Services

- University of Washington, Tacoma, Digital Collections

- Eastern Washington University Libraries Digital Collections

- University of Washington Bothell, Digital Collections and Services

West Virginia

Wisconsin

- University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, American Geographical Society Library, Digital Map Collection

- Maps of Wisconsin

- University of Wisconsin Digital Collections

- University of Wisconsin, The State of Wisconsin Collection

- Wisconsin Historical Society, Maps and Atlases in Our Collections

- University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, AGSL Digital Collections Portal

- Milwaukee Public Library, Recollection Wisconsin

- University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire, Special Collections and Archives

- University of Wisconsin, Superior, Special Collections Digital Resources

- InfoSoup

- Madison Public Library, History and Genealogy

- Wisconsin Historical Society, Central Wisconsin Digitization Project

- University of Wisconsin, River Falls, University Archives and Area Research Center

- Genealoger.com

- Wisconsin Digital Map Library

Wyoming

Thursday, May 15, 2014

Entropy and Genealogy

In physics, entropy is a state of disorder or randomness. It is often predicted as the end state of the universe as a state of equilibrium sometimes referred to as the heat death. From a practical standpoint, one of its many meanings illustrates the need to keep adding energy to any system (the energy available for work) or the system becomes disordered. I am beginning to think that this is a perfect analogy to genealogy. All of the unsourced, disorganized family trees represent the degree of entropy in the genealogical system. Unless outside work is added to the system, the amount of entropy tends to increase.

But it also has a more sinister implication. Let's suppose that my predictions about the future of genealogy are accurate. That is, that the large genealogy programs will continue to accumulate huge quantities of source records and that the search process will become automated. The analogy doesn't fit perfectly, but suppose that anyone interested in their ancestry could simply tap into one or more of these huge online databases and have the program find their "ancestors" back any number of generations automatically. Doesn't that spell the end of genealogy as we know it?

We may scoff at such a possibility, but just short thirty years ago, the idea that I could look at a screen and see my ancestry back 19 or 29 generations would have seemed like science fiction. We may wring out hands over the fact that there are still paper records out there waiting to be digitized, but we also need to understand that nearly all of us, I mean everyone on earth, now has a computerized record online. Here is an interesting quote:

In a sense, as genealogists, we are now working ourselves out of work. In order to keep going, we may have to become archaeologists and paleographers.

Now, just in case, after reading this, you decide that genealogy is no longer a challenge and you should go play shuffleboard or watch your grass grow for a challenge, then stop and think about all those so-called family trees out there. How accurate can they all be? Even with our huge supplies of records, it appears that entropy is winning the battle. We can quit and watch the heat death of genealogy or we can keep working and watch things slowly improve. There is a big difference between having the records available and knowing how to use them.

But it also has a more sinister implication. Let's suppose that my predictions about the future of genealogy are accurate. That is, that the large genealogy programs will continue to accumulate huge quantities of source records and that the search process will become automated. The analogy doesn't fit perfectly, but suppose that anyone interested in their ancestry could simply tap into one or more of these huge online databases and have the program find their "ancestors" back any number of generations automatically. Doesn't that spell the end of genealogy as we know it?

We may scoff at such a possibility, but just short thirty years ago, the idea that I could look at a screen and see my ancestry back 19 or 29 generations would have seemed like science fiction. We may wring out hands over the fact that there are still paper records out there waiting to be digitized, but we also need to understand that nearly all of us, I mean everyone on earth, now has a computerized record online. Here is an interesting quote:

There are almost as many cell-phone subscriptions (6.8 billion) as there are people on this earth (seven billion)—and it took a little more than 20 years for that to happen.In 2013, there were some 96 cell-phone service subscriptions for every 100 people in the world. Shouting is the likely the next-most widespread communications technique. See Quartz.Keeping track of all the people in the world right now is a data processing challenge and not impossible even with our present technology. So isn't genealogy pretty well already in the downward spiral? Right now, if I found a record that was not on the Internet someplace, I could take a digitized image of it with my smartphone and upload it in a matter of seconds. It seems to me that the main reasons why all the genealogically significant records of the world have not already been digitized are mainly social and political. But there is no question that all the present inhabitants of this world are likely to end up recorded on a computer somewhere.

In a sense, as genealogists, we are now working ourselves out of work. In order to keep going, we may have to become archaeologists and paleographers.

Now, just in case, after reading this, you decide that genealogy is no longer a challenge and you should go play shuffleboard or watch your grass grow for a challenge, then stop and think about all those so-called family trees out there. How accurate can they all be? Even with our huge supplies of records, it appears that entropy is winning the battle. We can quit and watch the heat death of genealogy or we can keep working and watch things slowly improve. There is a big difference between having the records available and knowing how to use them.

Wednesday, May 14, 2014

All Photographs Lie

There is an old saying that a photograph is worth 1000 words. I suggest that photographs are probably worth much more than 1000 words but that does not mean that the information is accurate or correct. I have put up notice that most genealogists accept photographs on their face totally and uncritically. A photograph is a source, just like any other source, and is subject to the same requirements of evaluation concerning reliability as any other source.

Let me give a hypothetical situation. Suppose that family members who have been bitterly fighting with each other throughout their lives all all come to the same funeral. A photograph taken at the funeral may show a happily smiling family group but would be utterly misleading as to the relationships between the parties. Further, the backgrounds and style of the photographs may be entirely misleading. Some of the very old photographs required long exposures and those photographs seldom, if ever, showed that individuals smiling. In one series of photos I found in an old collection, the women in different photos shared the same dress. Without seeing the related photographs, it would be impossible to know this fact. You may consider some of these examples to be trivial but we all have a tendency to identify our ancestors with their photographs.

I am not arguing that photographs are not useful in contributing historic information concerning ancestors. What I am saying is that photographs can be just as inaccurate or misleading as any other documentary source. The first important fact to realize is that the photographer chooses the subject matter, place and timing of the photograph. It is entirely possible for the photographer to frame the photo so as to cut it out what to the photographer are undesirable background objects or other people. To the extent that the photograph is controlled by the photographer it is a personal statement taken from the photographer's point of view rather than an objective historical document.

I recently discussed the ethics of altering existing historical photographs when making copies. There is a more serious issue about the process the photographer goes through in selecting and creating a photograph. One of the most famous photographers of our time is Ansell Adams. You might be surprised to know that he spent a great deal of time in the darkroom altering his original photographs. Today, we would call this photoshopping the image. If you have the opportunity to stand next to a gifted photographer and watch that person take photographs and then later, have the opportunity to view the same printed photographs, you may wonder whether or not you were actually present when the photographs were taken.

For this reason, most photographs are notable for what they do not show rather than what they do show. Sometimes photographs suggest relationships and activities that are entirely inconsistent with the traditional family story about the individual ancestor. For example, there may be photographs showing the ancestor enjoying the companionship of someone who was obviously not their spouse or in other situations showing activities that the ancestor would not normally be associated with. In some instances, these types of photographs were destroyed either by the ancestor or by close relatives who did not wish to show the ancestor in a negative light. Occasionally, some of these photos survive to create interesting historical issues.

At one point in the past a photograph could be used as conclusive evidence in a court case. However, that day has long since passed. Today, even with substantial supporting testimony photographs are always subject to a measure of skepticism.

In our modern age, I would guess that there is not one photograph that you can presently see in an advertisement that has not been altered in some way from the original. We are so used to seeing altered photographs that we do not even realize that some of them are so altered as to be totally imaginary.

As genealogists, we may make the mistake to believe that this process of altering photos originated with computers. In fact, since the first photo was taken the photographer has always been in control of the photograph both at the time was taken and during the developing and printing process.

It is always a good idea to take the time to critically evaluate each and every historical photograph. Not only may there be interesting information you may have missed with a superficial examination, there may also be inaccurate or incorrect traditional assumptions about the subjects of the photos that are questioned by the examination.

Let me give a hypothetical situation. Suppose that family members who have been bitterly fighting with each other throughout their lives all all come to the same funeral. A photograph taken at the funeral may show a happily smiling family group but would be utterly misleading as to the relationships between the parties. Further, the backgrounds and style of the photographs may be entirely misleading. Some of the very old photographs required long exposures and those photographs seldom, if ever, showed that individuals smiling. In one series of photos I found in an old collection, the women in different photos shared the same dress. Without seeing the related photographs, it would be impossible to know this fact. You may consider some of these examples to be trivial but we all have a tendency to identify our ancestors with their photographs.

I am not arguing that photographs are not useful in contributing historic information concerning ancestors. What I am saying is that photographs can be just as inaccurate or misleading as any other documentary source. The first important fact to realize is that the photographer chooses the subject matter, place and timing of the photograph. It is entirely possible for the photographer to frame the photo so as to cut it out what to the photographer are undesirable background objects or other people. To the extent that the photograph is controlled by the photographer it is a personal statement taken from the photographer's point of view rather than an objective historical document.

I recently discussed the ethics of altering existing historical photographs when making copies. There is a more serious issue about the process the photographer goes through in selecting and creating a photograph. One of the most famous photographers of our time is Ansell Adams. You might be surprised to know that he spent a great deal of time in the darkroom altering his original photographs. Today, we would call this photoshopping the image. If you have the opportunity to stand next to a gifted photographer and watch that person take photographs and then later, have the opportunity to view the same printed photographs, you may wonder whether or not you were actually present when the photographs were taken.

For this reason, most photographs are notable for what they do not show rather than what they do show. Sometimes photographs suggest relationships and activities that are entirely inconsistent with the traditional family story about the individual ancestor. For example, there may be photographs showing the ancestor enjoying the companionship of someone who was obviously not their spouse or in other situations showing activities that the ancestor would not normally be associated with. In some instances, these types of photographs were destroyed either by the ancestor or by close relatives who did not wish to show the ancestor in a negative light. Occasionally, some of these photos survive to create interesting historical issues.

At one point in the past a photograph could be used as conclusive evidence in a court case. However, that day has long since passed. Today, even with substantial supporting testimony photographs are always subject to a measure of skepticism.

In our modern age, I would guess that there is not one photograph that you can presently see in an advertisement that has not been altered in some way from the original. We are so used to seeing altered photographs that we do not even realize that some of them are so altered as to be totally imaginary.

As genealogists, we may make the mistake to believe that this process of altering photos originated with computers. In fact, since the first photo was taken the photographer has always been in control of the photograph both at the time was taken and during the developing and printing process.

It is always a good idea to take the time to critically evaluate each and every historical photograph. Not only may there be interesting information you may have missed with a superficial examination, there may also be inaccurate or incorrect traditional assumptions about the subjects of the photos that are questioned by the examination.

Tuesday, May 13, 2014

Digital Public Library of America adds 390,000 images from University of Florida

In a recent blog post, the Digital Public Library of America announced,

The George A. Smathers Libraries at the University of Florida (UF) have partnered with DPLA by contributing more than 390,000 items, including antique maps, rare books, manuscripts, photographs, oral histories, newspapers, and research publications. All will become accessible to DPLA’s global audience of students, teachers, scholars, developers, and the public.The significance of this acquisition to the genealogical community is illustrated by the following:

The Smathers Libraries collections will bring a new, diverse set of perspectives to DPLA’s holdings. For example, more than 150,000 issues of Florida and Caribbean newspapers, historical to current, provide insight into the news and history of Florida, the Caribbean, and circum-Caribbean.The records from the University of Florida will be added to the over 7 million items already in the DPLA.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)