While I was involved in digitizing records at the Maryland State Archives in Annapolis, Maryland for FamilySearch.org, I was interested to notice when typewriters were first used to record the records I was digitizing. A little bit of research I found the following from Wikipedia: Typewriter.

The first typewriter to be commercially successful was patented in 1868 by Americans Christopher Latham Sholes, Frank Haven Hall, Carlos Glidden and Samuel W. Soule in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, although Sholes soon disowned the machine and refused to use or even recommend it. It looked "like something like a cross between a piano and a kitchen table". The working prototype was made by the machinist Matthias Schwalbach. The patent (US 79,265) was sold for $12,000 to Densmore and Yost, who made an agreement with E. Remington and Sons (then famous as a manufacturer of sewing machines) to commercialize the machine as the Sholes and Glidden Type-Writer.

Here is an image of the Patent office model of the machine patented July 14, 1866, by Sholes, Glidden, and Soule.

As I worked at digitizing records, I watched the dates that the first typewritten documents appeared. Of course, I was not looking at all the documents, but I began to see typewritten documents in the mid to late 1880s. However, it was not until well into the 1900s that all of the documents began to be typed.

Why is this important for genealogical research? The simple answer is that anyone doing genealogical research will have to be able to read handwritten records for any research going into the 1800s. Granted, if you were born in the last thirty years, your "ancestors" back to your great-grandparents were probably born in the 1900s but extending research beyond that generation will inevitably require the ability to read handwritten documents.

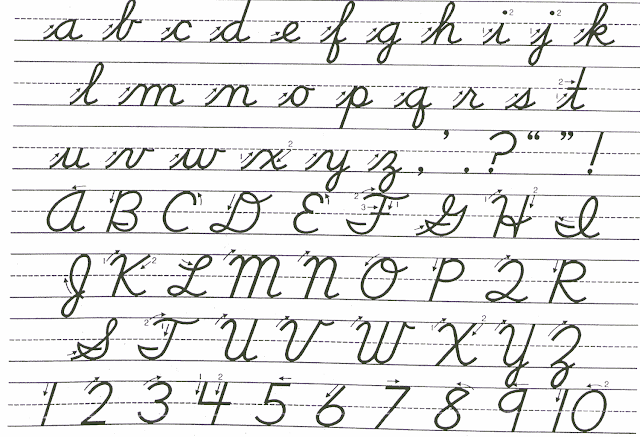

The basic issue in the United States is that even if cursive handwriting is taught in the school systems across the country, that does not mean that the students can read cursive documents. Here is an example of a modern cursive handwriting chart.

Compare this chart to this image of a letter written in 1936.

For a real-life example of what I am writing about, give this sample to one of your young family members or someone in grade school and ask them to read it to you.

Interestingly, much of the genealogical advertising and promotion today talks about involving the "youth" in family history and genealogy and at the same time uniformly ignores the fact that even many adults could not read a letter written in the 1930s. Here is another example from the 1940 U.S. Federal Census.

This would be considered to be easy to read by most genealogists.

If you want a real example of the challenge of reading old handwriting, you only need to go back to the mid-1800s.

Is there a solution? I think it is time that the larger genealogical community recognizes that doing genealogical research requires a bundle of individual skills that must be learned and that learning those skills takes considerable effort and time. I would suggest that more emphasis should be made on giving people the tools and opportunities to acquire those skills. This does not mean that we stop trying to involve the youth, but it does mean that we do not ignore and denigrate those who spend the time and effort to learn the skills that are essential to genealogical research.

Seems this would be a good project for BYU-Pathway Worldwide. Indeed, it should be part of a worldwide free program the gives all youth in the world the ability to read and write, both present records, as well as past literature. [Of the world population older than 15 years 86% are literate. . . .Globally however, large inequalities remain, notably between sub-Saharan Africa and the rest of the world. In Burkina Faso, Niger and South Sudan – the African countries at the bottom of the rank – literacy rates are still below 30%.] As noted by Elder Hartman Rector, Jr., of the First Quorum of the Seventy, Turning the Hearts, May 1981 Ensign, [We, then, are in the very serious business of attempting to save the earth or to keep it from being “wasted” when the Lord comes. . . . I personally believe that the writing of personal and family histories will do more to turn the hearts of the children to the fathers and the fathers to children than almost anything we can do.] A key, unused, critical, overlooked, global contact of individuals as family units having children; missionary preparation learning tool. Also seems like an excellent, inexpensive, but nevertheless comprehensive way of obtaining our own self-preservation from a promised curse from God.

ReplyDeleteCorrection: free program that gives all youth in the world . . .

DeleteEven though I'm old enough to have learned cursive in grade school, the Palmer Method, which I was taught is much clearer than the scribblings on many of the old documents that I've worked with. This 10-part class by Fritz Juengling Ph.D., might prove helpful. I participated in his week-long seminar on the same topic last November, and found it very beneficial. https://www.familysearch.org/help/helpcenter/lessons/latin-handwriting-1-introduction

ReplyDeleteI TOTALLY agree with you regarding youth working on this difficult and sacred endeavor!

ReplyDelete