Can you prove it? Is what you post in your family tree the truth? In the context of genealogical research, do either of these terms have any meaning? Can these questions even be answered? Genealogical research focuses on a limited part of the world's history; that part pertaining to family and individual histories. It is rare that a genealogical researcher puts their family history into the greater context of local, national, or world history. For example, do you think the pandemic that started sometime in the year 2020 had any kind of impact on you or your family? Do you think that the Flu Pandemic of 1918-1919 had any impact on you or your family? How many people in your ancestral families died during the years 1918 and 1919? Do you know how many of them died of the flu? Have you even thought about why your ancestors died? Obviously, if one of your direct line ancestors had died before having children, they would not be your ancestor.

What do these questions have to do with proof or truth? Let's take the cause of death as an example. Let's suppose in your research you discover records showing when and where your ancestor or relative died. Do you know how or why that person died? Why would that information be interesting or important? Did you know that a significant part of the greater genealogical research community is entirely motivated by discovering the causes of their ancestors' deaths? The reason is to determine if certain diseases are inherited and to further determine the frequency of inheritance. However, if you are doing such research, you will soon learn that medical diagnoses of the cause of death, going back in time, can be very unreliable. It is common that a person's death has multiple causes. Can we tell which of the causes was the "true" cause of death? Going back in time using the historical records available could you prove which of the potential causes of death were the true cause of death?

Historical "truth" depends entirely upon the accuracy and completeness of the preserved historical records. Since death certificates in the United States have been created only fairly recently, you are very unlikely to find a record stating the cause of death before around 1850 any place in the country and many states did not uniformly require death certificates until well into the 20th Century. The issues of historical and thereby genealogical proof and truth rely entirely on preserved historical records. Genealogical proof and truth are not abstract philosophical concepts, they are simply opinions and conclusions drawn from whatever historical records exist.

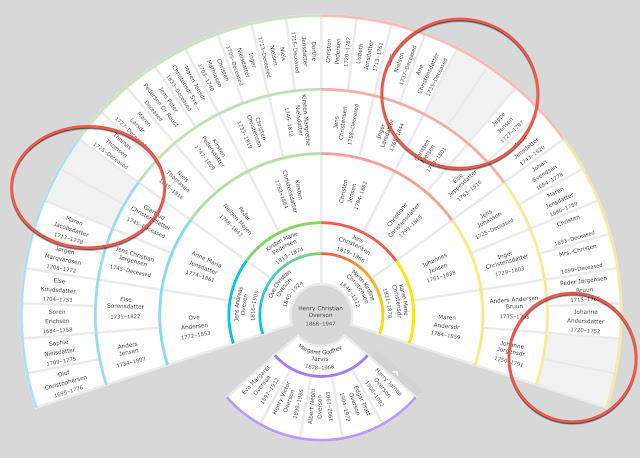

For example, continuing the cause of death issue, here is a death certificate for William De Friez dated January 27, 1918.

The cause of death is listed as lobar pneumonia. Here is an article explaining this cause of death.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). “Bacterial Pneumonia Caused Most Deaths in 1918 Influenza Pandemic,” September 22, 2015. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/bacterial-pneumonia-caused-most-deaths-1918-influenza-pandemic.

See also:

Brundage, John F., and G. Dennis Shanks. “Deaths from Bacterial Pneumonia during 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 14, no. 8 (August 2008): 1193–99. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1408.071313.

It is highly likely that although the cause of death was pneumonia, this person had the flu. So, what was the "true" cause of death? Quoting from the above article.

The majority of deaths during the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 were not caused by the influenza virus acting alone, report researchers from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health. Instead, most victims succumbed to bacterial pneumonia following influenza virus infection. The pneumonia was caused when bacteria that normally inhabit the nose and throat invaded the lungs along a pathway created when the virus destroyed the cells that line the bronchial tubes and lungs.

You might note that both of the articles above date from well before the present COVID-19 pandemic.

In the case of William De Friez there might be additional non-medical records that would tell us if he caught the flu, but they would not be reliable. By the way, the earliest death records from Utah generally start in 1898 with Salt Lake City death records starting in 1848, Logan in 1863 and Ogden in 1890. This person lived in Modena, Utah, a small settlement in Iron County along the Nevada border. The doctor who signed the death certificate did so in Cedar City, Utah about 52 miles away from Modena hence the note at the bottom of the certificate that says, "No Local Registrar."

Some of this additional information expands on and clarifies the information in the death certificate. Could I prove that William De Friez died of influenza? I might be able to infer or conclude that he did, but all we could safely conclude is what is written on the death certificate. However, he did die of a related disease during the flu pandemic.

Now, let me take this a step further. Let's suppose that for some reason the cause of death was an important factor in a lawsuit. Would there be enough evidence for a jury to conclude that the cause of death was pneumonia? Actually, in most instances, yes. A government document regularly prepared in the course of the creator's duties is an exception to the hearsay rule. There are several exceptions that cover this type of document. The doctor would not likely need to be a witness.

There is usually an inherent ambiguity in historical records. Almost every document is subject to more than one interpretation. You can claim that you have proved some genealogical relationship but the reality of historical records mandates that your "proof" is nothing more or less than your opinion subject to the discovery of additional records.

Part of the process of becoming a genealogist or historian is accommodating the evanescent nature of the preserved historical record. So please don't tell me about your proof or that you know your conclusion is true. Your proof may be valid but remember the limitations of relying entirely on a historical record.