Wednesday, August 31, 2016

A Look into Genealogical Source Evaluation: Let's Get Real

When I was very young, we used to have books of trading stamps. There were several varieties, but S and H Green Stamps were the most common. The idea persists today with the bar code cards many people carry around to obtain discounts from various merchants. We dutifully produce our bar code card although we aren't quite sure if we are getting anything in return. The difference with Green Stamps was that you could fill books of stamps and redeem them for actual products in S and H Green Stamp redemption locations or by mail.

Well, I think genealogy, in some cases, has become a game of pasting names into a book to get some, usually only partially defined, benefit such as "connecting with our ancestors" or whatever. Don't get me wrong, there are real, fundamentally important reasons for researching our ancestors, but there is a level of genealogical activity that is more interested in filling in the blank spaces then deriving any real value from what is produced. How do we get away from the Green Stamp approach to genealogy? May I suggest that a significant step will be to begin critically examining the information we acquire.

Unlike the generic nature of the trading stamp, our ancestors are not identical items to be pasted into an album or booklet. The real significance of the research comes at the point when you begin to realize that these were real people with real challenges and some significant problems. This realization only comes when you move beyond the superficial collection stage (aka the U.S. Census stage) and start to view your ancestors in their place in the vast sweep of history. In fact, it might be a good idea to start with your own place in history.

I can certainly work at the collection level in genealogy but I also know when I have moved past being a collector into considering the reality of the people I am researching. I think this change comes when I stop looking at my ancestors as blank spots on a fan chart and start asking questions about how much I know about their lives and their circumstances. Perhaps, we all need to spend more time thinking about our ancestor's lives as real people. I can treat genealogy like a puzzle where I look for pieces that fill in the gaps, or I can think of my ancestors as people who lived and died with all the experiences in between where my job becomes understanding and documenting their story.

How do I know this is an issue? When I am asked by researchers how many sources are needed for each person in their family tree.

I spent most of my life being paid to essentially do research. The underlying motivation of all this research was to prove that my clients were right and another attorney's clients were wrong. Of course, the opposing attorney was trying to prove the exact opposite. Some genealogists treat their research as if they were trying to prove a point and as I have written many time before, they adopt a whole hierarchy of levels of ways to "evaluate" the "evidence" and prove their conclusions. Generally, they also have clients that they are trying to represent. When I first started to get really serious about genealogy, I too thought about representing clients and getting paid for my research. But after a very few experiences in "representing clients" I realized that the concept of advocacy in genealogy defeated the ultimate interests in discovering the past.

Every historical document tells a story. If we get caught up in the legalistic evaluation of documents as primary and secondary, original or derivative, direct or indirect, then we a caught in the paradigm that at some point we are going to prevail and prove that we are right and the rest of the world is wrong. Maybe, we should look at documents as individual stories, some are more reliable than others, but each tells us something about the people we are researching. Maybe we will never know the "full story" but we can gather everything we can and come to our own conclusions. But if we ignore this crucial step of critical evaluation, we are shunted back to the level of collectors filling in empty spaces on a chart.

It was interesting to me that after many years of conducting initial client interviews, I could tell rather quickly whether or not my potential client was telling me the truth. What was interesting, especially early on with criminal cases, was that after representing hundreds of criminal defendants, I only had two that I could remember who actually were telling me the truth and in one of those cases, my client was trying to lie to me. I distinctly remember one civil jury trial where I suddenly realized that my client was lying, the opposing client was lying and the opposing attorney was lying. I felt sorry for the jury.

Let's look at a specific issue genealogical issue from the FamilySearch.org Family Tree for an example of critically examining the documents. Here is an individual I have been researching lately. I used part of this same family as an example in my last post.

You can see that he was supposed to be born in "Wellwood Corners, Mexico, New York" and an exact date is recorded. Let's look at the sources so far.

All of these sources except the Legacy NFS source were added by me. How do we know when James J. Wellwood was born? Well, the 1900 U.S. Federal Census document says that he was born in December of 1810. The 1850 U.S. Federal Census document indicates he was born about 1813. The FindAGrave.com entry indicates that his birth date is unknown. Lastly, the Legacy new.FamilySearch (NFS) source says that family records give a birth date of 8 November 1811 in Mexico, Oswego, New York.

When and where was he born? The real answer at this point is we don't know. Does this matter? Did James J. Wellwood or Welwood really live? Does the fact that the FindAGrave.com website has a photo of his grave marker make any difference? Where do we go from here? Here is what the 1900 U.S. Federal Census has to say.

Here is the actual Census record.

It might help to know that there is a place called Wellwood in New York and that there is note in the FindAGrave.com entry as follows: "Wellwood, also known as South Mexico, was named in honor of James Wellwood who settled there in 1838." From here the plot thickens as they say. Actually, the first Wellwood in the area was likely named John who arrived with his wife Esther Tanner Wellwood in Mexico, New York in 1838 from Rhode Island. The 1900 U.S. Census shows that some one said that James's father was born in England and his mother was born in Connecticut. John Wellwood, James's father is recorded as being born in New York and his mother as being born in Rhode Island.

OK, this is enough to illustrate my point. If I were just copying out the entries from these various "sources" it should be apparent that the family dates and identities would be an unsolvable mess. Somewhere in this mess, there is something reliable, but right now, a lot more research needs to be done. Could we fill in our stamp book with the names and dates we already have? Yes, we could but we are very, very likely wrong about most, if not all of the details and we are still not sure who these people were. Although we may never resolve some of the differences in dates, we can get to the point where we know about this family in a way that makes them distinctive individuals.

Let's get real in our research.

Tuesday, August 30, 2016

Tell Us Where You Got the Information

It looks like it is time to get going about genealogical sources again. Here is my definition of a genealogical source.

The place or person from whence the information was obtainedA source is not a citation. Here is one definition of a citation.

More precisely, a citation is an abbreviated alphanumeric expression embedded in the body of an intellectual work that denotes an entry in the bibliographic references section of the work for the purpose of acknowledging the relevance of the works of others to the topic of discussion at the spot where the citation appears. See Wikipedia: Citation.We often use the phrase, "cite your sources" to indicate that when you obtain information from somewhere, it is proper to let others know where the information came from. If we use some form of specific information without attributing the source, we are plagiarizing the source. When I quote someone or something, I indent the quotation and then provide a citation or a link to the original statement or source.

I am not concerned here about the "form of citation" used by genealogists. Most genealogists are not academically educated scholars and they are not writing for formal publication in a genealogical journal. Neither are they providing a professional proof statement to a client. But everyone obtains their information from somewhere even it is personal experience and we are entitled to know where they got their information.

There is a measure of discussion among some genealogists about what is and what is not a proper "source." We get into quasi-legalistic arguments over primary and secondary sources and all such nonsense. The truth is that the artificial distinction between a "primary" source and a "secondary" source has been created to try and resolve the problem that all historical sources, no matter how they are derived, are subject to scrutiny and could be unreliable. Just because someone was there when an event occurred and recorded their impressions does not mean what they wrote or said was reliable. It is always possible that any particular witness to an event is lying.

Why do we need to know where historical information came from? There are entire books written on this subject. Some genealogists in their zeal to provide "accurate" information tell people not to reveal their sources if the source was unreliable. For example, I have heard more than once that a certain type of record, such as a Family Group Record created by a family member or an index is unreliable and "should not be used as a source." Hmm. Personally, I would rather have you tell me you got your information from your aunt or from an index than not. The real problem is when information is entered and no mention is made of where that particular information was obtained.

Here is an example from the FamilySearch.org Family Tree.

Here, Sarah Remington is listed as having been married to two men, both with the same surname. The first entry is to a C. Wellwood and the second entry is to a James J. Wellwood. The first entry has an approximate marriage date and place, the second entry has no information about the marriage. Someone added the first entry and entered the information about the marriage but left no source information. So far, I have been able to document and cite the second marriage to James J. Wellwood with several sources. But I have yet to find even one reference to a marriage to C. Wellwood. If the person had simply told me that they copied the information from a Family Group Record, that would help me to evaluate the accuracy of the information. I don't really care at this point whether the person provided me with an academically acceptable citation according the Chicago Manual of Style, I would just like to know where the information came from with enough detail to find the source.

Absent this source information, I have to spend my time trying to discover where the information came from and whether or not it is reliable. Even if the said they copied the marriage off of a gum wrapper that would at least give me an idea where to start.

So let's get over this idea that we should exclude any source references at all simply because we judge them to be unreliable. Let's stop telling people that such and such is "not a source" and should not be included in a list of sources. If they got the information from from someplace we would consider to be unreliable we can disregard it. But it is always better to know than not know.

But what about conflicting information? Wow, this is a loaded question. Let's not omit anything for the reason that we personally disagree with the content.

Monday, August 29, 2016

Is that website down right now?

I was doing what I usually do all day and into the night, writing a presentation or a blog post or whatever and I tried to access Ancestry.com. Here is what I got:

My reaction to this type of message is automatic. I try to log in again by retyping the URL. I got the same results. I tried again to make sure. Most of this was done so automatically, I did not really think about it. Then I opened FamilySearch.org where I have a link to Ancestry.com and tried the link. Nothing happened. My next step was also automatic, but I had started thinking that maybe the website was really down.

I did a quick online Google search to see if my inability to connect was local or general. There are websites that watch that sort of thing. One is "Is It Down Right Now?" www.iidrn.com. Here is a screenshot of the report.

Yes, the website had been down for about 33 minutes. What do I do then? Start doing something else, of course.

By the way, it came up in about two more minutes of waiting.

My reaction to this type of message is automatic. I try to log in again by retyping the URL. I got the same results. I tried again to make sure. Most of this was done so automatically, I did not really think about it. Then I opened FamilySearch.org where I have a link to Ancestry.com and tried the link. Nothing happened. My next step was also automatic, but I had started thinking that maybe the website was really down.

I did a quick online Google search to see if my inability to connect was local or general. There are websites that watch that sort of thing. One is "Is It Down Right Now?" www.iidrn.com. Here is a screenshot of the report.

Yes, the website had been down for about 33 minutes. What do I do then? Start doing something else, of course.

By the way, it came up in about two more minutes of waiting.

The Family History Guide looking for Sponsorships

The L3C is designed to make it easier for socially oriented businesses to attract investments from foundations and additional money from private investors.[8]Unlike the traditional LLC, the L3C’s articles of organization are required by law to mirror the federal tax standards for program-related investing. [9] A program-related investment (PRI) is one way in which foundations can satisfy their obligation under the Tax Reform Act of 1969 to distribute at least 5% of their assets every year for charitable purposes.[7] While foundations usually meet this requirement through grants, investments in L3Cs and charities that qualify as PRIs can also fulfill the requirement while allowing the foundations to receive a return.[10]In short, The Family History Guide is now actively seeking sponsorships. Quoting from a recent notice sent to me,

This is your special invitation … to help thousands of people around the world find and connect with their family roots, and have your logo and website link placed on tens of thousands of desktops, tablets and other devices in over 140 countries!

Let me introduce myself - I'm Bob Ives, COO and co-founder of The Family History Guide, L3C. We are a low-profit company dedicated to one mission: to greatly increase the number of people actively involved in family history worldwide, and to make everyone’s family history journey easier, more efficient, and more rewarding. Family history involvement builds a stronger sense of identity, culture, and history, and we are proud to be at the forefront of building this involvement worldwide. We have no paid employees and are staffed with volunteers who share our vision. We accomplish our mission by providing a free website, The Family History Guide

(www.thefhguide.com)

with a unique just-in-time learning model that is revolutionizing how people find and connect to their roots.To explain how this will work, here is a listed description of the process, again from the notice sent to me.

In keeping with our mission statement, we have no advertising on our website. Still, we have ongoing business expenses that must be met. To address these needs, we are introducing our Sponsorship Campaign, which enables individuals, companies and organizations to donate to this important cause, as well as benefit from PRI's (Program-Related Investments) and tax incentives such as advertising deductions.

The Family History Guide is

- A free website visited by people in over 140 countries.

- On the main Family Search portal page in over 4,800 Family History Centers and libraries, on over 10,000 desktops and thousands more personal computers worldwide.

- A semi-finalist in the RootsTech 2016 Innovator Showdown.

- Used for training family history consultants at the BYU Family History Library, the Riverton, Utah Family History Library, and many other libraries across the U.S.

- A partner with Family Search, the largest free family history company in the world, and part of the Family Search App Gallery.

- Part of an L3C company that qualifies to receive PRI's from foundations and other organizations.

- A website where your logo may qualify as an advertising expenditure for your organization, company, or foundation.

- A company of all volunteers who do not receive compensation for their time or expenses.

How you can get involved and help this worldwide effort

You or your organization can help us reach our goal of continuing to provide a free website that enables more people, worldwide, to succeed in family history. Your donation will receive special recognition on the The Family History Guide website: your logo will be prominently displayed and directly linked back to you, plus other benefits depending upon your participation level.

Become an individual donor, partner or sponsor with The Family History Guide today!

Click here to get started.I do not usually get directly involved in fundraising efforts, but in this case, I am making an exception because of the inherent value of this free program.

Sunday, August 28, 2016

Using Smart Technology to Jump-Start Your Genealogical Research: Part Two

Automated Record Hints

One of the most impressive, new genealogical technologies to emerge in the last few years has been the advent of automated searches that provide extensive record hints matching the individuals in your online family tree with original sources. Included in this expansive technology is the ability to suggest connections with others that share the same ancestors in their own family trees. All four of the large, online genealogical database programs have implemented this new technology and even extended it to some of their subsidiary websites.

This rapidly developing technology has revolutionized the process of finding information about ancestral families for many users, particularly those with families from the United States, the British Isles and Canada. As the technology develops and more and more of the records are included in the automated searches, the process will become even more valuable to the genealogical researcher. In may cases today, especially for those whose more recent ancestors lived in the United States, sources are found identifying relatives back about 150 to 200 years with great accuracy.

This outstanding technology began with record hints from Ancestry.com called the "Shaky Leaf Hints." Significant, ground-breaking improvements to the accuracy and coverage of the technology were implemented by MyHeritage.com and subsequently, the other websites increased both the incidence and accuracy of their own record hints. The technology is not always 100% accurate and does take some level of evaluation by the user, but by and large it has measurably increased the overall accuracy of the content of the online family trees.

The essential ingredient to facilitate this new technology is that the user enter some basic information into an online family tree associated with each website. Acceptance of the record hints has been dependent on the level of sophistication of the users. Many of the users of the websites have failed to add the sources to their own entries even though they are automatically provided and the process of adding the sources is relatively simple. There is also a significant level of resistance to the idea of maintaining more than one database, so if the user has a family tree in one program, there is a level of resistance in establishing another family tree in another program.

Another rather interesting issue with the implementation of the record hints is the surprising and mistaken impression that many people seem to have that all of the large online, genealogical database programs have the same records. Each of the websites has its own unique records. Of course, the basic limiting factor of the record hint technology is that it only works with indexed records and each of the websites is limited to the records on the website. Fortunately for the researcher, the number of indexed records is increasing extremely rapidly.

The method of marking the existence of a record hint varies with each of the websites. Here are some screenshots showing the various markers in each of the programs with an arrow indicating the icon indicating a record hint.

FamilySearch.org

Ancestry.com

MyHeritage.com

Findmypast.com

The way the record hints are handled by each of the programs varies, but the principle is the same. The program suggests a record hint and the user is then called upon to evaluate the suggested source and attach it with the new information or individuals to the user's online family tree in that particular program. The one remaining challenge is the ability to adequately move the information found from one family tree to one in another program. There are a few possibilities but by and large source must be copies one at a time and the information added to the target family tree. The user has to learn each of the methods of attaching and utilizing the information found for each website.

In some cases, the number of record hints can be overwhelming but this only points out the fact that the technology is advancing rapidly and the amount of information being made available is impressive.

Here is the previous post in this series.

http://genealogysstar.blogspot.com/2016/08/using-smart-technology-to-jump-start.html

Saturday, August 27, 2016

Researching Beyond Census Records

It is so simple and reassuring to find someone in a U.S. Census record. Between 1850 and 1940, it is almost a given that anyone in the U.S. can be found with a minimum of effort. Oh, you say, until you can't find them. Well, I found my Great-Uncle Allen Benedict Tanner and his family in the 1880 U.S. Federal Census by the simple expediency of reading through every page of the Census record in the small community of Beaver, Beaver, Utah. By the way, there are only 36 pages in that particular enumeration district, so it only took a few minutes to find the family.

The problem is that when you can't find your family in the U.S. Census where do you go? What do you do? What if you also strike out with searches on FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com? I should mention that when I tried to search on FamilySearch.org after I found the record by looking at every page, I did a search for "Allen B Tanner" in Beaver, Beaver, Utah and the search engine failed to find him or his family. So had I not already found him through the page by page search, I might have come to the conclusion that "he wasn't in the 1880 U.S. Census." This points out another important rule: always search the original records when they are available.

In short, doing genealogical research is a lot more than census searches and finding a family in the U.S. Census is sometimes a lot more than a census search also. Did I mention that I found my Grandfather in the 1920 U.S. Census when he was indexed as "Tamer" rather than "Tanner?"

The suggestion here is that there are lots of records about your ancestors other than just those in the U.S. Census. For example, Allen Benedict Tanner has twenty sources attached and I know that the number is only a fraction of the total number of places this particular Tanner family is mentioned in records. Just looking down the list already in the FamilySearch.org Family Tree, I could add in about three times that many sources if I had the time and inclination. But you say, so what? Who cares? And what difference does it make if there is one source or fifty?

Genealogical research is not a numbers game. We are not out to set some kind of record for adding sources to a family. There are no extra points for each source added. So why not stop with the one U.S. Census record or so that establishes the family and leave it at that?

By the way, this is a serious question and one that is posed to me regularly. I am regularly asked "How many sources is enough to add to someone in the Family Tree." My answer is always the same, "All of them." Just yesterday, I was getting frustrated with not being able to find a certain family in either FamilySearch.org or Ancestry.com. I did a general Google search and found an extensive biography of the father of the family with a long list of sources.

Is there a specific place to go if you cannot find an individual ancestor or family in the U.S. Census? Not really. The general rule is begin your search with marriage records as they are the most reliably recorded type of record. I eventually found yesterday's difficult family in cemetery records. I might also point out that you aren't through searching until you have looked at every type of record listed in the FamilySearch.org Research Wiki and the FamilySearch.org Catalog. I mean every single type of record listed. But usually, you can focus on church records or civil records to find most families.

When things get tough, the tough get going.

Friday, August 26, 2016

How accurate are historical records?

A recent local news article caught my eye, "Roy woman struggling to prove she's alive after government declares her dead." This story highlights a common problem faced by genealogists: conflicting source records. The Utah woman in the article has been fighting with the U.S. Government for over two years when the Social Security Administration reported her dead and her bank and other entities began to close accounts and try to collect for overpayment.

From the genealogical standpoint, we commonly find names misspelled, dates incorrectly recorded, people wrongly identified and myriad of other errors that cannot be corrected and must be dealt with. The list of possible errors also involves simple issues such as the transposition of numbers in dates to the intentional understatement or overstatement of ages. It is also not too uncommon to find where record keepers were faced with or created outright lies.

One of the most common issues and iconic for genealogists, is the fact that Census records are routinely off at least one year in the estimated age and birth date of the people listed. This is caused by the fact that the Census records are officially calculated from the "date of the census" which may affect the calculation of the age or birth date due to the actual date of birth being either before or after the official census date.

Are you bothered by the inconsistency in the records? Do you ignore the fact that the records are inconsistent and adopt one record as the "correct" source or can you live with the inconsistency? Ralph Waldo Emerson is reported to have said, in part, "A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds..." Perhaps, we need to try to avoid foolish consistency and realize that historical records can be contradictory.

Let's suppose that you find that a newspaper obituary and the grave marker disagree on the date of death. What do you do? Is there really any possibility or controversy as in the news article above, that the person is really dead? If not, then from a genealogical standpoint, what is the issue? One of the most important aspects of any form of historical research is to increase the breadth of our searches along with the depth. In the case I just cited, if the death date is crucial to identifying the right individual or for some other reason, then the answer is to do more research and find the will or the probate case in the court records. But if the actual date does not matter then why spend time trying to fight with inconsistency?

Too many times, I find people who are obsessed with finding a particular date. I have one friend who has spent a huge amount of time trying to find a death date and place for a relative. Perhaps it is time to realize that he is dead and get on with other research. It is always possible that the date and place of death were never recorded for some reason such as the fact that he was lost at sea or wandered off into the desert or mountains and died.

This whole issue points out the need for research that includes more sources than just one. There is wisdom in the admonition that in the mouth of two or three witnesses shall every word be established. See 1 Timothy 5:19.

Thursday, August 25, 2016

Can You Hear Me? Can You Hear Me? Comments on VR

|

| By I,, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2225868 |

|

| By Kobel Feature Photos (Frankfort, Indiana) / State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30423797 |

Even if VR becomes so ubiquitous that it replaces the manual controls of common appliances, the range of commands needed to operate, say a microwave oven, are so simple and limited as to make the problem somewhat trivial. Genealogy is not simple and what we type and record is far from the directions to heat some soup for 30 seconds.

As I have written in the past, I have been using VR for years off and on. There have been tremendous advances made in the accuracy and utility of the products, but for genealogists, we are just about at the very beginning of the development. Let me demonstrate the problem. Here is a rather simple quote from my family tree.

Name

Thomas Parkinson

Sex

Male

BirthNot complicated at all, is it? Now, using a very sophisticated VR program, without making any corrections, here is what I get:

12 December 1830

Farcet, Huntingdonshire, England, United Kingdom

Christening

12 January 1831

Ramsey, Huntingdonshire, England

Death

3 March 1906

Beaver, Beaver, Utah, United States

Burial

5 March 1906

Mountain View Cemetery, Beaver, Beaver, Utah, United States

Name

Thomas Parkinson

Sex

Earth

12 December 1830

Carson, Huntingdon Shire, England, United Kingdom

Christening

12 January 1831

Ramsey, Huntington Shire, England

Death

3 March 1906

Fever, Beaver, Utah, United States

Burial

5 March 1906

Mountain View Cemetery, beaver, beaver, Utah, United States

Now, there are commands that could resolve a few of these issues, but the reality is that I can accurately type the entire entry in much less time, with a higher degree of accuracy than I am willing to spend trying to get the VR program to make all the adjustments and correct all the bad entries. It does not really help me to go back to the keyboard and try to correct the entries. The reality is that while I am typing, I am making a lot of mistakes. Most of those I can correct with one or two keystrokes. But with VR, I am forced to use a whole bevy of commands, most of which will end up making it ever harder to correct the final product.

If I were simply writing a letter or an email, I could use the VR program and probable get as close as I needed to with only a few minor corrections, but that is not what I do all day. My operation of the computer involves a highly complex set of instructions that include a lot of clicking and dragging items from one place on the screen to another. To give oral commands to do something as simple as dragging and dropping an image and then formatting it, would require many commands and my frustration level would be enormous.

Even if I had a quick and easy way to use VR to move from field to field in a genealogy program, how long would it take me to train the program correctly for every place name, i.e. changing from Huntingdon Shire to Huntingdonshire? As it is, I have an extra line feed in the second Burial entry above, that I cannot get rid of using the keyboard, how could I do the same thing with oral commands if I cannot do it with my keyboard and trackpad? To correct that formatting issue, I have to go into the HTML and edit it directly.

Some years ago, a friend of mine had a car that gave audible, voice warnings. One particularly annoying warning said, "Your door is ajar." Of course, every time the car said that, we both said, "The door isn't a jar, it is a door." But you can begin to see the problem. Language usage is highly complex and even if computers get to the point of functioning like they do in some movies, they will still be annoying at times and blatantly wrong at other times, just as humans are.

VR is a wonderful tool but we have to realize that just because something is useful in one way or another does not mean that it the universal replacement for everything. I recall the scene in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home when Scotty is confronted with an old Macintosh computer. He talks to it and of course it doesn't respond, so he says "The keyboard, how quaint." But I am guessing that he would have had a very difficult time entering some complex commands solely using VR as demonstrated by the furious typing that ensues in the movie. By the way, the old Mac would not have the computer power to process the commands that Scotty was trying to enter.

In making these observations, I am not disparaging VR. Here is the last paragraph of my post, entirely using VR.

As genealogist, we need to be open to new technology and adapted [adapt it] to our working methodology. We also need to realize, that not all new technology translates into advantages for accomplishing our genealogical goals. Voice recognition is a powerful tool but it is not quite ready to take over the entire child [field] of interfacing with a computer.

Now, after dictating that paragraph, I went back and made the corrections which are shown in brackets and in red. The errors were real words and not caught by the spell checking capability of my computer. When the spell checker or, in this case, VR substitutes real words, making the corrections much more difficult to detect the typos and make the corrections.

My last note. VR usually refers to "voice recognition." But recently, it is coming to more commonly refer to "virtual reality." Even this type of confusion makes using both types of VR difficult.

Even if I had a quick and easy way to use VR to move from field to field in a genealogy program, how long would it take me to train the program correctly for every place name, i.e. changing from Huntingdon Shire to Huntingdonshire? As it is, I have an extra line feed in the second Burial entry above, that I cannot get rid of using the keyboard, how could I do the same thing with oral commands if I cannot do it with my keyboard and trackpad? To correct that formatting issue, I have to go into the HTML and edit it directly.

Some years ago, a friend of mine had a car that gave audible, voice warnings. One particularly annoying warning said, "Your door is ajar." Of course, every time the car said that, we both said, "The door isn't a jar, it is a door." But you can begin to see the problem. Language usage is highly complex and even if computers get to the point of functioning like they do in some movies, they will still be annoying at times and blatantly wrong at other times, just as humans are.

VR is a wonderful tool but we have to realize that just because something is useful in one way or another does not mean that it the universal replacement for everything. I recall the scene in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home when Scotty is confronted with an old Macintosh computer. He talks to it and of course it doesn't respond, so he says "The keyboard, how quaint." But I am guessing that he would have had a very difficult time entering some complex commands solely using VR as demonstrated by the furious typing that ensues in the movie. By the way, the old Mac would not have the computer power to process the commands that Scotty was trying to enter.

In making these observations, I am not disparaging VR. Here is the last paragraph of my post, entirely using VR.

As genealogist, we need to be open to new technology and adapted [adapt it] to our working methodology. We also need to realize, that not all new technology translates into advantages for accomplishing our genealogical goals. Voice recognition is a powerful tool but it is not quite ready to take over the entire child [field] of interfacing with a computer.

Now, after dictating that paragraph, I went back and made the corrections which are shown in brackets and in red. The errors were real words and not caught by the spell checking capability of my computer. When the spell checker or, in this case, VR substitutes real words, making the corrections much more difficult to detect the typos and make the corrections.

My last note. VR usually refers to "voice recognition." But recently, it is coming to more commonly refer to "virtual reality." Even this type of confusion makes using both types of VR difficult.

Wednesday, August 24, 2016

Looking back to the origins of Genealogy's Star

My first blog post on Genealogy's Star blog was two short paragraphs about the FamilySearch Research Wiki.

Since that small beginning, I have written and published 4468 posts and have kept writing now for almost eight years. When I wrote that first short blog post, I had no idea how extensively writing online would affect my life. Genealogically speaking, I have come a long way since that first, very tentative, offering.

Probably the most interesting part of the whole experience has been meeting so many wonderful people. Of course, if you know me, you realize that if I am not writing, I am probably talking. So one of the spinoffs of the writing experience has been teaching a steady stream of classes and presentations.

As an additional benefit of writing this blog, I have been asked to participate as a blogger at the annual RootsTech conference in Salt Lake City, Utah. Now, that we live in Provo, about an hour south of downtown Salt Lake, it is not quite as much of a production to attend the conference, but it is still a highlight of the year. My participation has turned out to involve the entire week of the conference, starting with the Brigham Young University Family History Technology Workshop on Tuesday and the Innovator Summit on Wednesday. This next year will probably be even more interesting than past years. The past two years, I have concentrated more on writing and meeting than presenting, but I have still had a constant schedule of meetings during all of the conferences and parts.

Just as a side note, you may want to go to RootsTech.org and keep updated on the conference scheduled for February 8 - 11, 2017. Hotel rooms tend to fill up for the conference and it is a good idea to plan way ahead.

Of course, the most dramatic change that has come in part from my involvement in genealogy is our move to Provo and my involvement with the Brigham Young University Family History Library. I have seven additional live, online webinars to present in September, 2016 and the spin off of this constant stream of webinars has been even more far reaching than the blogs. By posting the webinars on Google's YouTube on the BYU Family History Library Channel, I have seen a steady increase in the impact of this more immediate media outlet.

One interesting side effect of moving to Provo was that I almost completely stopped being invited to speak at conferences around the U.S. and Canada. In reality, that turned out to be a benefit, because now, I spend my time writing presentations for video output. But I have been involved in a lot of local conferences, in fact, both my wife and I are teach three classes each this Saturday for the Provo Grandview South Stake here in Provo.

Now another word about the name of this blog. If I had it to do over again, I would probably choose a different name. I was mostly thinking of an analogy to a guiding star or the sense that the term "star" is used by newspapers, particularly in Arizona. But I soon was embarrassed to realize my choice was somewhat presumptuous, but by that time, I was committed with the name and ran with it. Well, here we are, still writing away.

You would think I would run out of topics, but in reality I have long lists of topics to write on that I haven't had time to get to yet. When I run out of things to say, I will let you know.

Since that small beginning, I have written and published 4468 posts and have kept writing now for almost eight years. When I wrote that first short blog post, I had no idea how extensively writing online would affect my life. Genealogically speaking, I have come a long way since that first, very tentative, offering.

Probably the most interesting part of the whole experience has been meeting so many wonderful people. Of course, if you know me, you realize that if I am not writing, I am probably talking. So one of the spinoffs of the writing experience has been teaching a steady stream of classes and presentations.

As an additional benefit of writing this blog, I have been asked to participate as a blogger at the annual RootsTech conference in Salt Lake City, Utah. Now, that we live in Provo, about an hour south of downtown Salt Lake, it is not quite as much of a production to attend the conference, but it is still a highlight of the year. My participation has turned out to involve the entire week of the conference, starting with the Brigham Young University Family History Technology Workshop on Tuesday and the Innovator Summit on Wednesday. This next year will probably be even more interesting than past years. The past two years, I have concentrated more on writing and meeting than presenting, but I have still had a constant schedule of meetings during all of the conferences and parts.

Just as a side note, you may want to go to RootsTech.org and keep updated on the conference scheduled for February 8 - 11, 2017. Hotel rooms tend to fill up for the conference and it is a good idea to plan way ahead.

Of course, the most dramatic change that has come in part from my involvement in genealogy is our move to Provo and my involvement with the Brigham Young University Family History Library. I have seven additional live, online webinars to present in September, 2016 and the spin off of this constant stream of webinars has been even more far reaching than the blogs. By posting the webinars on Google's YouTube on the BYU Family History Library Channel, I have seen a steady increase in the impact of this more immediate media outlet.

One interesting side effect of moving to Provo was that I almost completely stopped being invited to speak at conferences around the U.S. and Canada. In reality, that turned out to be a benefit, because now, I spend my time writing presentations for video output. But I have been involved in a lot of local conferences, in fact, both my wife and I are teach three classes each this Saturday for the Provo Grandview South Stake here in Provo.

Now another word about the name of this blog. If I had it to do over again, I would probably choose a different name. I was mostly thinking of an analogy to a guiding star or the sense that the term "star" is used by newspapers, particularly in Arizona. But I soon was embarrassed to realize my choice was somewhat presumptuous, but by that time, I was committed with the name and ran with it. Well, here we are, still writing away.

You would think I would run out of topics, but in reality I have long lists of topics to write on that I haven't had time to get to yet. When I run out of things to say, I will let you know.

Tuesday, August 23, 2016

Using Smart Technology to Jump-Start Your Genealogical Research: Part One

Genealogical research can seem tedious and time consuming and it often is exactly that. But we are presently going through a life changing technological revolution that is fundamentally changing the way we do our work. It can now be truthfully said that smart technology can jump-start your genealogical research.

Using the new "smart" technology is a lot more involved than merely searching on the Internet or using a word processing program on your computer. Some of the technological springboards available right now include the following:

- Automated record hint capabilities that find suggested original sources

- Online document storage and organization programs

- Source citation programs that automatically format your citations and create bibliographies

- News aggregator programs that keep you informed of posts to blogs and other websites

- Billions of digitized source documents in thousands of archive websites

- Comprehensive mapping and gazetteer programs that open windows into historical locations

- Huge online geographic names databases

- A multitude of devices from digital cameras to smartphones, tablets and other computer devices can take images of documents for research and store them or share them with your other devices.

I am going to start with something very basic: digitizing our paper records. The advantages of having digital copies of our paper records may not seem evident to those who are not "connected" in the current sense of the word.

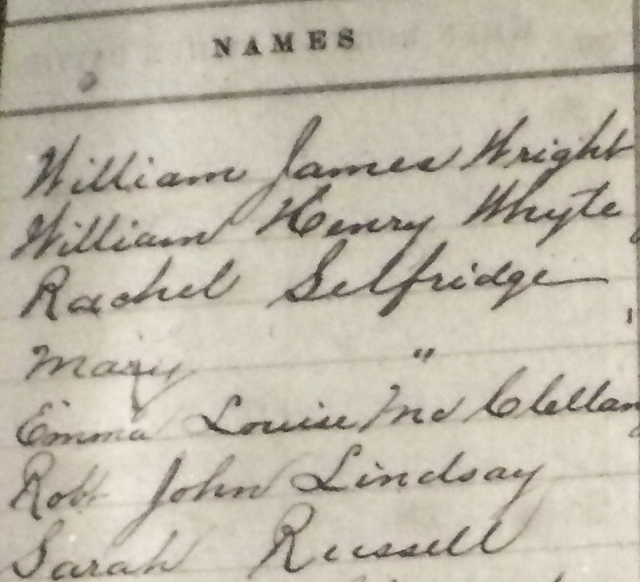

Smartphone cameras are quickly becoming ubiquitous. But what may not be obvious is that the same smartphone or cell phone camera you use to take snapshots of family members and family gatherings, can be used to gather highly readable copies of documents you find as you do research or already have in paper files. Here is an example of a photo of a page from a parish register I took from a microfilm reader:

This was taken with my 8 Megapixel iPhone camera. There is a "hot spot" where the reader's light was reflected from the surface of the old style reader, but the image is highly readable and useful. Here is a magnified section of the image:

Although the image would not be considered to be "archive quality," it is readable and very useful. I could get better images with a better camera, but the iPhone camera was the one I had with me when I was doing research in the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah. We may find ourselves in a situation where we find genealogically interesting documents or records, such as a chance visit to a cemetery or archive, and we can use this new technology to take photos on the spur of the moment.

Now, let's extend this technology a lot further. Once I have an image in my smartphone, I can immediately share it with relatives or upload it online. For example, Ancestry.com has its Shoebox app. Here is a description of the app from Ancestry:

Shoebox turns your iPhone or Android into a high-quality photo scanner. With Shoebox, you can quickly scan paper photos, add important historical information like dates and places, and upload directly to your Ancestry.com family tree.You can also edit the photo and its description:

Editing dates, places, tags, and captions is easy. After you’ve cropped a photo, you will be taken to a “Edit details” page. Use the icons at the bottom to tag family members, date your photo, add a location, and write your own description.You can also do many of the same things with the FamilySearch.org Memories App. Here is a description of the features of the Memories app:

- Store memories for free forever, deep within the FamilySearch vaults.

- Pick up where you left off on any device since the app automatically syncs to FamilySearch.org.

- Take family memories wherever you go—the app works even without Internet access.

- Snap photos of any family moment, such as recitals, dates, graduations, reunions, and memorials, and add them to your family tree.

- Use the app to take photos of old photos and documents too!

- Use the app to interview family members and record audio details of their life stories and favorite memories.

- Write family stories, jokes, and sayings with the keyboard, or use the mic key to record what you say.

- Enrich written stories by adding descriptive photos.

- Identify relatives in photos, stories, and recordings to add those memories automatically to their collection in Family Tree.

There are several other such convenient programs that can add this functionality to your smartphone.

Stay tuned for the next installment in this series.

Monday, August 22, 2016

Homage to the Agricultural Laboror

One of the realities of history and genealogy is that there are a lot more common people than there are rich, famous or royalty. The American fascination with royalty has hardly diminished. I can trace back almost every one of my family lines on the FamilySearch.org Family Tree and eventually someone has connected that family line to a royal line in Europe. However, careful review of the English census records usually reveals that my ancestors were tradesmen or "Agricultural Laborers" and had no claims to royal descent.

This topic came up recently when I traced one family line to a widow in the English Census who was identified as a pauper and the widow of an agricultural laborer or "AL." For some reason, it touched my heart that my own ancestors had suffered so much deprivation and poverty. But it did explain why they ultimately immigrated to Australia.

OK, so it is possible that one or two of your ancestral lines can be traced back to royalty. After all, kings and rich guys had children so why couldn't there be one or two in your own family lines? Well, for those of us who can trace some of your lines back a ways in America, it is entirely possible to find one or two who connect to a Gateway Ancestors with documented royal connections. If you have aspirations of royal descent, then you need to be very familiar with the term "gateway ancestors." I suggest you start with a FamilySearch post by my friend, Nathan Murphy, entitled "Documenting Royal Ancestry, written back in October of 2015. Here is a key quote from that article:

If the immigrant in your family is a valid gateway, you are on track to documenting royal ancestry. If your immigrant is not on the list, the royal lineage presented to you is probably underproven or false.I might mention that this whole concept goes to claims of descent from an "Indian Princess" also. But in that case, I would suggest a comprehensive DNA test before you start trying to prove you have access to living on an Indian Reservation.

Personally, I am becoming more and more impressed with the tenacity of my poor and very common ancestors who apparently survived the difficulties of being agricultural laborers and became my own ancestors.

Sunday, August 21, 2016

Do I need a "genealogy program" to do my genealogy?

This is not another post about paper vs. computerized genealogy. My question addresses a serious issue that goes to the heart of what most people consider "doing their genealogy." At one end of the spectrum we have "professional" genealogists who, after doing intensive research, write "proof statements" based on the "Genealogical Proof Standard." The process is usually described something like this:

The Genealogical Proof Standard is the standard set by the genealogical field to build a solid case, especially when there is no direct evidence providing an answer, or when there are conflicts in the evidence.See Amazon ad for the following book,

Rose, Christine. Genealogical Proof Standard: Building a Solid Case. San Jose, Calif: CR Publications, 2014.

The fact of the matter is that a "professional genealogist" could do everything they do for clients using a word processor and a copy machine or other scanning device. In fact, they could do without a word processing program and still use a typewriter. There is nothing about doing genealogical research that would have to rely on a computer or any particular computer program. Professional genealogists would not accept a "computer generated" genealogy as an acceptable professional document.

But what about online research and digitized sources? Of course, almost all genealogists now recognized the need to do some research online, but in the end, there is still a major issue with the completeness of research if you rely only on online sources.

I acknowledge that this level of genealogical research is still necessary in some instances and because this is the case, there is a real issue about the need for the spectrum of "genealogy" programs now available. Some have taken umbrage with my use of the term "program." I use the term in its most general sense, i.e. a set of instructions given to a computer. From my standpoint, any time I turn on any electronic device, it is using a program. You can call it what you want, app, routine, subroutine, to me they are all "programs."

Many of the computer programs stylized as "genealogy specific" are in effect specialized database programs written in a particular computer language. Each of these programs reflect the understanding of the programmers about what a potential genealogical user would like to store about his or her family. But none of these programs actually do genealogy. They are simply elaborate methods of storing information. A professional genealogist would immediately reject almost all of the programs because the source and citation style does not conform to a recognizable standard. For example, none of the currently available genealogical database programs will automatically produce a source citation that conforms to the Chicago Manual of Style. Why would I use such a program if I have to rewrite every one of the citations the programs produces?

If a computer program developer develops a program either for individual use on one computer or for general use online and calls it a "genealogy" program, does that mean that the program is necessary to do genealogy? If my primary activity as a "genealogist" is writing Case Studies and Proof Arguments, isn't my primary genealogy program a word processor?

What if I don't really care about proof statements or client reports? What if all I want to do is see my family in a pedigree chart? Do I really need a program to do that?

I think the answer to all this is simple. What we do as genealogists depends on our expectations and the end product of our research. The various electronically designed devices and programs may be tools, but our main activity involves our individual research and writing. I use the tools to save time and to organize my research. But it is always a good idea to question whether or not using a particular program is helping me to achieve my goals.

Saturday, August 20, 2016

The Challenges of Adding Sources to Family Trees -- Part One: The Historical Reality

Genealogy is not immune to movements, fashions and fads. Some of these turn out to be beneficial to individual genealogists, others not so much. In the past, a considerable amount of the genealogical effort went into compiling "surname books," the generic term for compiled family histories that either detailed the descendants of a remote ancestor or the ancestors of a more recent person. Many of these books were compiled from "personal information" or undocumented sources. I have at least five of these family history books about branches of my family tree and none of the five cite any significant number of sources. Errors in these publications have proliferated into the current crop of online family tree.

Until quite recently, the concept of documenting the sources of information referred to in compiling a family tree was almost completely missing from in the entire genealogical community. In fact, adding sources was actively discouraged by the paper forms used to record family information. Here is a screenshot of a "family group record" actively used for recording research between about 1940 and the present day which I selected at random from the FamilySearch.org website Historical Record Collections.

I certainly don't fault the people who were compiling and submitting these forms for their lack of documentation. Here is a close up of the section allowed for source citations.

The number for the item identified as a "Tanner Gen" does not appear in the FamilySearch.org Catalog. The number is very likely as modified form of a method of marking the relationships of the people in a book to the beginning or most prominent individual. The point here is that this old, and still commonly used form does not encourage documentation and the documentation that was provided is entirely insufficient to identify the source. Some of the more sophisticated genealogical researchers used the backs of the forms to type in a list of sources; but this rarely happened.

It would be impossible to accurately determine how many of the now-existing, online family trees owe their genesis to these undocumented family group records. As far as I know, the individual shown above, Harry Tanner, is not my relative. There are several unrelated Tanner families in the United States from England and Switzerland. By the way, there are over 2,500 individuals named "Harry Tanner" listed in the FamilySearch.org Family Tree and incidentally, there is no such place as Hermon, Connecticut where the wife is supposed to have been from. I did find a reference to this same Harry Tanner in an Ancestry.com family tree and the source for the information was listed as the Ancestral File, a compilation of these same family group records.

So the cycle is repeated. The original reference is in an undocumented surname book which is then copied to a family group record and then incorporated in the Ancestral File which is used to add the individual, unchanged, to an online family tree on the Ancestry.com website.

Here is the entry for Harry Tanner from the FamilySearch.org Ancestral File.

Interestingly, the entry in the Ancestral File gives you a way to cite the reference:

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, "Ancestral File," database, FamilySearch(https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/2:1:M46S-NY4 : accessed 2016-08-20), entry for Harry TANNER.If I were to believe this undocumented entry, I would find that indeed Harry Tanner and I are related as the pedigree shown in the Ancestral File goes back to our common ancestor. Unfortunately, the entries in the FamilySearch.org Family Tree about this common ancestor are presently duplicative and unsupported. In fact, as it now stands, the descendants of the common ancestor do not include this particular family line. To date, there is no documented connection between the early, colonial Tanner family in Connecticut and my Tanner family in Rhode Island.

This phase of genealogical research in which documentation was almost uniformly lacking is still with with us. As I have noted on many occasions, most of the online family trees are lacking in documentation and as I have demonstrated, the origin of some of the information is highly unreliable.

The idea behind this series is to examine the present cultural attitudes and physical limitations placed on researchers who wish to adequately document their research.

Friday, August 19, 2016

Editing limitations added to the FamilySearch Family History Wiki

The following announcement was made by FamilySearch concerning the FamilySearch.org Family History Wiki (previously called the Research Wiki):

For many years, the FamilySearch wiki allowed open editing for everyone. In recent weeks, however, the wiki has been plagued by spammers taking advantage of this system. The wiki team is now asking that you register as an editor by filling out a simple survey form. You will be cleared by the wiki team and given editing rights. The process may take up to 48 hours but probably will be much quicker.

- Find the survey form by clicking the link in the orange message at the top of any wiki page.

- Please remember to keep your family history center FamilySearch wiki web page current!

- If you have questions about your web page, please see the article “A New Look for Your Family History Center Web Page.”

- If you need help with your web page, contact wikisupport@FamilySearch.org.

I might point out that the Research or Family History Wiki has always only been open to editing by registered users of the FamilySearch.org website. I might also point out that the Family Tree is also a wiki based product and some of us believe that some of the additions to the Family Tree also constitute "spam" in a general use of the term. If both programs want to maintain their integrity in a highly politicized and religiously persecuted world, then controls on the contributors were and will be inevitable. Maybe it is time to examine the "contributions" of the "registered" users of both programs?

The following notification has been put on each of the pages of the Family History Research Wiki.

The red letters say:

If you are unable to edit the wiki after logging in, you will need to request editing rights using this form. You will be notified when editing rights are granted.Not too long ago, I wrote a post about the fact that most of the contributing and editing of the Research Wiki was moving "in house." In response, I got a series of protestations that editing and contributing were still open to the general, genealogical community. However, communication regarding the Research Wiki has become entirely internalized in an "invitation only" Yammer forum.

Currently, the number of active users or contributors has crashed to just over 200 in the last 30 days. In the past the number has been close to 1000.

The value and content of the Research Wiki have not been diminished at all by this lull in activity. I am guessing that most of the slowdown in activity is a result of the fact that adding useful information that is not already present is getting to be a much harder task and requires a much higher level of expertise. As a side note, I am expecting the FamilySearch.org Family Tree to go through the same cycle of activity.

Thursday, August 18, 2016

Department of Justice files antitrust suits against heir location companies

News stories are appearing about a United States, Department of Justice investigation of antitrust violations among heir location firms around the country. The news broke here locally in Utah with the filing of an antitrust case against Salt Lake City based company called Kemp and Associates. See bigstory.ap.org "Utah firm that finds distant heirs accused in antitrust case." Quoting from the U.S. Department of Justice website about the first lawsuits:

Bradley N. Davis, president of Brandenburger & Davis, and his firm will plead guilty to conspiring between 2003 and 2012 to eliminate competition in the heir location services industry. Heir location services firms identify people who may be entitled to an inheritance from the estate of a relative who died without a will. The heir location services firms then help heirs secure their inheritances in exchange for a contingency fee paid out of the inheritances they are due to receive.

“The defendants conspired for nearly a decade to enrich themselves at the expense of beneficiaries,” said Assistant Attorney General Baer. “Heirs of relatives who died without a will deserve better. Working with the FBI and our other law enforcement partners, the Antitrust Division will continue to hold the leaders of companies that corrupt the competitive process accountable for their crimes.”

Brandenburger & Davis has agreed to pay an $890,000 criminal fine for its role in the conspiracy. In a separate plea agreement, Davis and the Antitrust Division have jointly agreed to allow the court to determine an appropriate criminal sentence. In addition, both the company and Davis have agreed to assist the government in its investigation. The charge was filed today in the U.S. District Court of the Northern District of Illinois. The terms of the plea agreements are subject to approval of the court.An heir location firm generally agrees to attempt to find the unknown heirs of a deceased person for a percentage of the estate should the heirs be located. The Utah article explains the process:

The allegations stem from a Justice Department investigation into anti-competitive practices in the industry in which companies track down distant relations when someone dies without a will or close family.

Workers sift through probate filings in search of recently deceased people who may have missing or unknown heirs.

For competitive reasons, details of the estate are typically withheld until the heir signs a contract with the company.

The firms then use court records, genealogical documents and other public data to help them secure the inheritance in exchange for part of the assets.

The industry defends its practices, saying it has helped heirs secure millions of dollars in inheritances they otherwise would never have known about.Even though I practiced probate law for many years and represented clients in probate cases, I never had the need to employ one of these companies. The appeal of this type of investigation is in representing very large estates where the recovery would warrant a sizable fee. Those who perform heir investigation services do not have to be attorneys neither are they regulated. Although this type of antitrust action may result in their regulation by the government in the future. This is a rather rare occurrence, when a genealogy-related activity makes the national news.

The Colonial Williamsburg Education Resource Library

I has been some time since I last wrote about the History.org website maintained by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. This website is a good example of the type of online resource that is unknown to genealogists in general and almost never referenced in genealogy conferences. I have found that nearly the entire genealogy community is woefully nearsighted when it comes to online and library resources.

Not only does Colonial Williamsburg have a significant number of online resources, it has an extensive library, the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library.

If you are doing colonial research or looking at ancestors in Virginia, you need to be aware of the expanded opportunities that exist in public, university and private libraries.

Additionally, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation has expanded their educational opportunities.

See the following article for a more detailed explanation.

OUR ONLINE HISTORY LIBRARY IS NOW YOURS FOR FREE!

Wednesday, August 17, 2016

Technology Marches On

Genealogists in general are not early adopters as is shown by the discussion about the old Personal Ancestral File program that ensued as result of my recent post. But your individual attitude towards technological change has almost no effect on the changes.

One of the most pervasive mechanisms driving computer technology today has been the Intel's constant upgrading of their chip sets. Once again, Intel has announced a new generation of chips to be introduced in the Fall of 2016, the seventh-generation code named Kaby Lake. As a result of the upgraded chip set, you can also expect the major operating systems such as Windows and Mac OS X to be upgraded.

What does this mean for most genealogists? Probably not much. But as the computer chips continue to evolve and the Internet programmers take advantage of the new offerings, older computers will at some point no longer be able to run the newer software as it is released.

See "Intel’s 7th Generation Kaby Lake Core i7-7700K CPU Leaked – Core i7-7500U and Core M7-7Y75 For Mobility Detailed."

Read more: http://wccftech.com/intel-kaby-lake-core-i7-7700k-cpu-leaked/#ixzz4Hb4EzMrd

To add a little more interest to the tech changes, Google is apparently developing another new operating system code named, Fuschia. Speculation is that the new operating system may or may not replace the present Chrome and Android operating systems. See "What is Google Fuchsia?" You might want to note that the Google Chromebook computers do not run any installed genealogy programs since they only run programs that are online on the Internet, that includes Personal Ancestral File.

Google is also in the news about its new Apple FaceTime competitor, Google Duo. I am in the process of installing this new app on my iPhone and testing it out. It is supposed to allow video calls between both Android and iOS devices. I do not find that it can be installed on an iPad yet however.

Tuesday, August 16, 2016

What is a Genealogy Program? No Simple Answer

In response to my recent Top Ten list, I got a challenge that the programs I listed weren't really "genealogy" programs and the title to my post was misleading. Hmm. It seems when I do "genealogy" I must be doing something different than the commentator. I guess I should have confined myself to listing only those "programs" that have the word "genealogy" in their title. Wait a minute, I don't know of any program that has the word "genealogy" in its title. Wait again, what about the term "family history?" That isn't much help either.

Maybe I should have confined my list only to those programs that help me find my ancestors? No, that doesn't work because doing a Google search for your ancestors is a fundamental step in starting any genealogical research project. So I must list Google as a "genealogy" program even if the word "genealogy" is not usually associated with Google per se.

What about the other "programs" I listed? Apparently, there is also an issue with calling them programs at all. The new word, "app" is rapidly replacing the word "program" but the word "app" is merely a shortened form of the word "application." Whatever you want to call a list of instructions to a computer is alright with me. Here is the definition of a "program."

A computer program is a collection of instructions that performs a specific task when executed by a computer. A computer requires programs to function, and typically executes the program's instructions in a central processing unit.That definition seems to me to be pretty inclusive. If I use Google Search to search for genealogy information, when does it become a "genealogy program?" Eventually? Never? I think the answer verges on the metaphysical. When a program becomes included in my or your own list of "genealogy" seems to me to be arbitrary.

Computer program - Wikipedia, the free encyclopediahttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computer_program

Let's talk about programs that create a family tree and store information about your family. I could use a dedicated program, such as some of the ones I have mentioned, or I could use a general purpose program such as Google Docs or Google Drive. Isn't it either interesting or perhaps important to know which of these types of programs we use for genealogy? But, you argue, that doesn't make them genealogy programs. Well, there we are. I happen to consider what I use to be useful for genealogy and ergo, for me, they are genealogy programs.

OK, so I admit it. The title of the blog should have qualified my list to say something like, "The Top Ten Programs (or whatever you want to call them) that I use when I am doing what I like to call, genealogy (your opinion may differ)." I didn't realize I was being genealogically, politically incorrect.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)